Kafka 101

This is a guest article by Stanislav Kozlovski, an Apache Kafka Committer. If you would like to connect with Stanislav, you can do so on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Originally developed in LinkedIn during 2011, Apache Kafka is one of the most popular open-source Apache projects out there. So far it has had a total of 24 notable releases and most intriguingly, its code base has grown at an average rate of 24% throughout each of those releases.

Kafka is a distributed streaming platform serving as the internet’s de-facto standard for real-time data streaming.

Its development is path-dependent on the problems LinkedIn hit at the time. As they were one of the first companies to hit large scale distributed systems problems, they noticed the common problem of uncontrolled microservice proliferation:

To fix the growing complexity of service-to-service and persistence store permutations, they opted to develop a single platform which can serve as the source of truth.

Apache Kafka is a distributed system that was meant to solve the service coordination problem. Its vision is to be used as the central nervous system inside a company - somewhere where data goes, is processed/transformed and is consumed by other downstream systems (data warehouses, indices, microservices, etc.).

Therefore, it is optimized for accommodating large throughput (millions of messages a second) while storing a lot of data (terabytes)

The Log

The data in the system is stored in topics. The fundamental basis of a topic is the log - a simple ordered data structure which stores records sequentially.

The log underpins a lot of Kafka’s fundamental properties, so it is prudent for us to focus more on it.

It’s immutable and has O(1) writes and reads (as long as they’re from the tail or head). Therefore the speed of accessing its data doesn’t degrade the larger the log gets and, due to its immutability, it’s efficient for concurrent reads.

But despite these benefits, the key benefit of the log and perhaps the chief reason it was chosen for Kafka is because it is optimized for HDDs.

HDDs are very efficient with relation to linear reads and writes, and due to the log’s structure - linear reads/writes are the main thing you perform on it!

As we covered in our S3 article, HDDs have become 6,000,000,000 times cheaper (inflation-adjusted) per byte since their inception. Kafka’s architecture is optimized for a cost-efficient on-premise deployment of a system that stores a lot of data while also being very performant!

Performance

A well-optimized on-premise Kafka deployment usually ends up being bottlenecked on the network, which is to say that it scales to many gigabytes per second of read and write throughput.

How does it achieve such performance? There are multiple optimizations - some macro and others micro.

Persistence to Disk

Kafka actually stores all of its records to disk and doesn’t keep anything explicitly in memory.

Kafka’s protocol groups messages together. This allows network requests to group messages together and reduce network overhead.

The server, in turn, persists chunk of messages in one go - a linear HDD write. Consumers then fetch large linear chunks at once.

Linear reads/writes on a disk can be fast. HDDs are commonly discussed as slow because they are when you do numerous disk seeks, since you’re bottlenecked on the physical movement of the drive’s head as it moves to the new location. With a linear read/write, this isn’t a problem as you continuously read/write data with the head’s movement.

Going a step further - said linear operations are heavily optimized by the OS.

Read-ahead optimizations prefetch large block multiples before they’re requested and stores them in memory, resulting in the next read not touching the disk.

Write-behind optimizations group small logical writes into big physical writes - Kafka does not use fsync, its writes get written to disk asynchronously.

Pagecache

Modern OSes cache the disk in free RAM. This is called pagecache.

Since Kafka stores messages in a standardized binary format unmodified throughout the whole flow (producer ➡ broker ➡ consumer), it can make use of the zero-copy optimization.

Zero-copy, somewhat misleadingly named, is when the OS copies data from the pagecache directly to a socket, effectively bypassing Kafka’s JVM entirely. There are still copies of the data being made - but they’re reduced. This saves you a few extra copies and user <-> kernel mode switches.

While it sounds cool, it’s unlikely the zero-copy plays a large role in optimizing Kafka due to two main reasons - first, CPU is rarely the bottleneck in well-optimized Kafka deployments, so the lack of in-memory copies doesn’t buy you a lot of resources.

Secondly, encryption and SSL/TLS (a must for all production deployments) already prohibit Kafka from using zero-copy due to modifying the message throughout its path. Despite this, Kafka still performs.

Back to Basics

The nodes in the distributed system are called brokers.

Every topic is split into partitions, and the partitions themselves are replicated N times (according to the replication factor) into N replicas for durability and availability purposes.

A simple analogy is that just how the basic storage unit in an operating system is a file, the basic storage unit in Kafka is a replica (of a partition).

Each replica is nothing more than a few files itself, each of which embody the log data structure and sequentially form a larger log. Each record in the log is denoted by a specific offset, which is simply a monotonically-increasing number.

The replication is leader-based, which is to say that only a single broker leads a certain partition at a time.

Every partition has a set of replicas (called the “replica set”). A replica can be in two states - in-sync or out-of-sync. As the name suggests, out-of-sync replicas are ones that don’t have the latest data for the partition.

Writes

Writes can only go to that leader, which then asynchronously replicates the data to the N-1 followers.

Clients that write data are called producers. Producers can configure the durability guarantees they want to have during writes via the “acks” property which denotes how many brokers have to acknowledge a write before the response is returned to the client.

- acks=0 - the producer won’t even wait for a response from the broker, it immediately considers the write successful

- acks=1 - a response is sent to the producer when the leader acknowledges the record (persists it to disk).

- acks=all (the default) - a response is sent to the producer only when all of the in-sync replicas persist the record.

To further control the acks=all property and ensure it doesn’t regress to an acks=1 property when there is only one in-sync replica, the `min.insync.replicas` setting exists to denote the minimum number of in-sync replicas required to acknowledge a write that’s configured with `acks=all`.

Reads

Clients that read data are called consumers. Similarly, they’re client applications that use the Kafka library to read data from there and do some processing on it.

Kafka Consumers have the ability to read from any replica, and are typically configured to read from the closest one in the network topology.

Consumers form so-called consumer groups, which are simply a bunch of consumers who are logically grouped and synchronized together. They synchronize each other through talking to the broker - they are not connected to one another. They persist their progress (up to what offset they’ve consumed from any given partition) in a particular partition of a special Kafka topic called `__consumer_offsets`. The broker that is the leader of the partition acts as the so-called Group Coordinator for that consumer group, and it is this Coordinator that is responsible for maintaining the consumer group membership and liveliness.

The records in any single partition are ordered within it. Consumers are guaranteed to read it in the right order. To ensure that the order is preserved, the consumer group protocol ensures that no two consumers in the same consumer group can read from the same partition.

There can be many different consumer groups reading from the same topic.

One core reason that made Kafka win over the traditional message bus technologies was precisely this decoupling of producer and consumer clients. In some systems, the messages would be deleted the moment they’re consumed, which creates coupling. If the consumers were slow, the system may risk running out of memory and impacting the producers. Kafka doesn’t suffer from this issue because it persists the data to disk, and due to the aforementioned optimizations, it can still remain performant.

Protocol

Clients connect to the brokers via TCP using the Kafka protocol.

The producer/consumer clients are simple Java libraries that implement the Kafka protocol. Implementations exist in virtually every other language out there.

Fault Tolerance

An Apache Kafka cluster always has one broker who is the active Controller of the cluster. The Controller supports all kinds of administrative actions that require a single source of truth, like creating and deleting topics, adding partitions to topics, reassigning partition replicas.

Its most impactful responsibility is handling leader election of each partition. Because all the centralized metadata about the cluster is processed by the Controller, it decides when and to what broker a partition’s leadership changes to. This is most notable in failover cases where a leader broker dies, or even when it is shutting down. In both of these cases, the Controller reacts by gracefully switching the partition leadership to another broker in the replica set.

Consensus

Any distributed system requires consensus - the act of picking exactly one broker to be the controller at any given time is fundamentally a distributed consensus problem.

Kafka historically outsourced consensus to ZooKeeper. When starting the cluster up, every broker would race to register the `/controller` zNode and the first one to do so would be crowned the controller. Similarly, when the current Controller died - the first broker to register the zNode subsequently would be the new controller.

Kafka used to persist all sorts of metadata in ZooKeeper, including the alive set of brokers, the topic names and their partition count, as well as the partition assignments.

Kafka also used to heavily leverage ZooKeeper’s watch mechanism, which would notify a subscriber whenever a certain zNode changed.

For the last few years, Kafka has actively been moving away from ZooKeeper towards its own consensus mechanism called KRaft (“Kafka Raft”).

It is a dialect of Raft with a few differences, heavily influenced by Kafka’s existing replication protocol. Most basically said, it extends the Kafka replication protocol with a few Raft-related features.

A key realization is that the cluster’s metadata can be easily expressed in a regular log through the ordered record of events that happened in the cluster. Brokers could then replay these events to build up to the latest state of the system.

In this new model, Kafka has a quorum of N controllers (usually 3). These brokers host a special topic called the metadata topic (“__cluster_metadata”).

This topic has a single partition whose leader election is managed by Raft (as opposed to the Controller for every other topic). The leader of the partition becomes the currently active Controller. The other controllers act as hot standbys, storing the latest metadata in memory.

All regular brokers replicate this topic too. Instead of having to directly communicate to the controller, they asynchronously update their metadata simply by keeping up with the topic’s latest records.

KRaft supports two modes of deployment - combined and isolated mode. Combined is similar to the model under ZooKeeper, where a broker can serve the role of both a regular broker and a controller at once. Isolated is when the controllers are deployed solely as controllers and serve no other function besides that.

The first Kafka release that featured a production-ready KRaft version was Kafka 3.3, released in October 2022. ZooKeeper is set to be completely removed in the next major Kafka release - 4.0 (expected around Q3 2024).

Tiered Storage

As mentioned earlier, Kafka’s architecture was optimized for a cost-efficient on-premise deployment. Since then, the proliferation of cloud has certainly changed the way we architect software.

One of the architectural choices that become glaringly nonoptimal once Kafka took off was its decision to colocate the storage with the broker. Brokers host all of the data on their local disk, which brings a few challenges with it, especially at scale.

First, as Kafka is meant to be the central nervous system of a company’s architecture, it’s not uncommon to want to have brokers that store 3TB of historical data on them - this results in 9TB total assuming the default replication factor of 3.

When a broker has close to 10TB of data locally, you start to see issues when things go wrong.

One evident problem is handling ungraceful shutdowns - when a broker recovers from an ungraceful shutdown, it has to rebuild all the local log index files associated with its partitions in a process called log recovery. With a 10TB disk, this can take hours if not days in certain cases.

Another problem is historical reads. Kafka’s performance relies heavily on the assumption that consumers are reading from the tail of the log, which in practice means they’re reading from memory due to the pagecache containing the latest produced data. If a consumer fetches historical data, this usually forces the Kafka broker to read it from the HDD. HDDs have historically been stuck at 120 IOPS for a long time, which is to say that it’s really easy to exhaust that resource. This means the consumers compete with the producers for IOPS and once that gets depleted, performance tanks.

The IOPS problem becomes amplified during hard failure scenarios. If a broker has a hard failure of its disk, it starts up with an empty disk and has to replicate all that 10TB of data from scratch. This process can take up to a day itself depending on the free bandwidth, and during that time said broker is issuing historical reads on many other brokers. One such failure amplifies into a lot of historical reads - the impact can be much more severe if a whole availability zone experiences a hard failure.

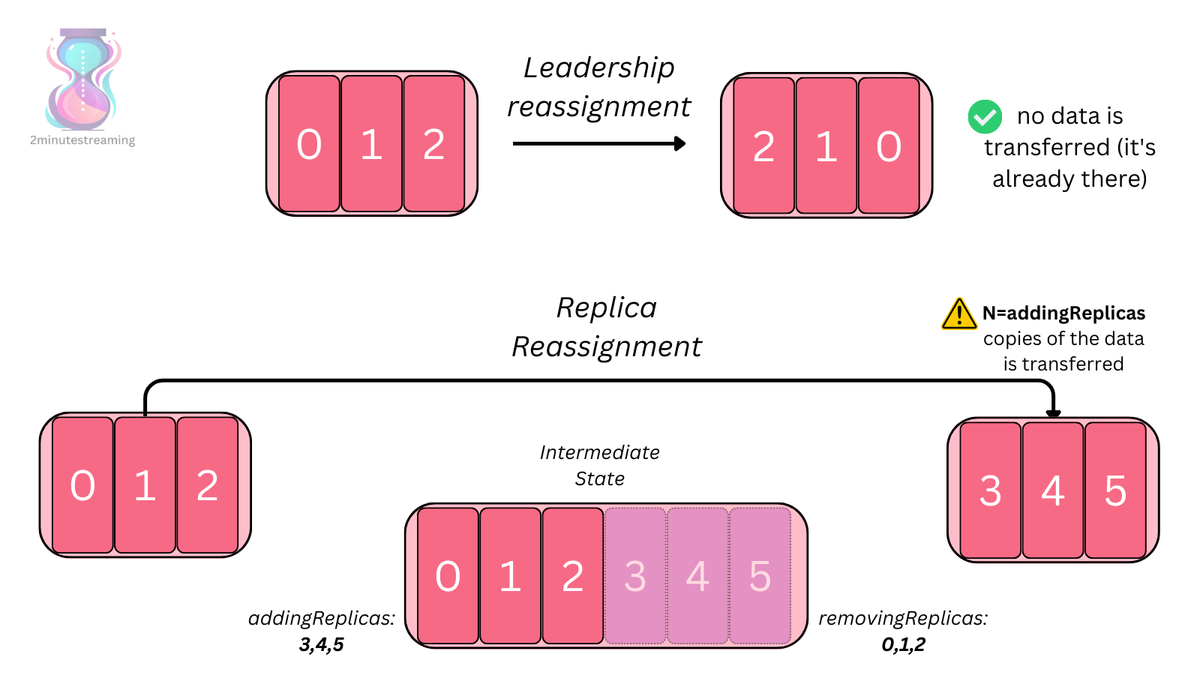

The final case where the amount of data becomes problematic is in rebalancing scenarios. Kafka allows you to reassign the replicas of any partition - and that involves moving all of the data along with it.

As a simple example, take a partition that has a replica set of brokers [0,1,2]. Usually, the first replica is the leader - hence broker 0 is leading that partition. If you want to introduce new replicas, they will start off as an out of sync replica and have to read all of the partition’s data from the leader 0 before becoming an in-sync replica.

If you add more nodes to your Kafka cluster, for example, you have to reassign some subset of partition replicas to those new brokers, otherwise they would remain empty. The reassignment process has the receiving broker copy all of the data for the given replicas, which not only can use up precious IOPS itself due to its historical nature, but also take a very long time.

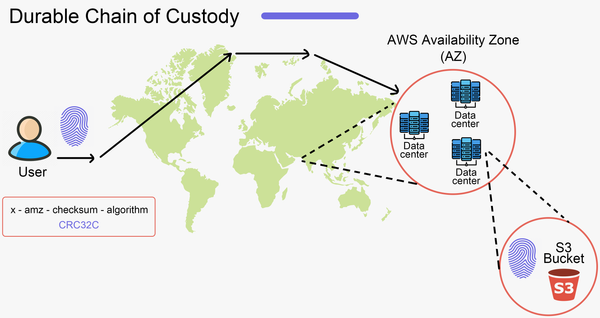

Apache Kafka is solving all of these issues by introducing a feature called Tiered Storage - the simple idea of storing most of the data in a remote object store (e.g S3). While still in Early Access, Kafka now has two tiers of storage - the hot local storage and the cold remote storage - both abstracted away seamlessly.

In this new mode, leader brokers are responsible for tiering the data into the object store. Once tiered, both leader and follower brokers can read from the object store to serve historical data.

This feature nicely solves all the aforementioned problems as brokers no longer need to copy massive amounts of data and historical reads no longer exhaust IOPS. Tests from development showed a 43% producer performance improvement when historical consumers were present. Depending on the object store, this can result in saving cost too as you’re outsourcing the replication and durability guarantees.

Auxiliary Systems

Rebalancing

Reassigning partitions is a key necessity in any Kafka cluster that’s seeing non-trivial usage.

Since it’s a distributed system with varying client workloads, the system can easily develop hot spots or inefficient resource distribution throughout its lifecycle.

To alleviate this, Kafka exposes a low-level API that allows you to reassign partitions. Exposing the functionality is the easy part - the hard part is deciding what to move where.

Essentially the NP-hard Bin Packing problem at heart, the community has developed a few tools and even a fully-fledged component to handle this.

Cruise Control, originally also developed at LinkedIn, is an open-source component which reads all brokers’ metrics from a Kafka topic, builds an in-memory model of the cluster and runs that model through a greedy heuristic bin-packing algorithm to optimize the model via reassigning partitions. Once it has computed a more efficient model, it begins incrementally applying it to the cluster by leveraging the low-level Kafka reassignment API.

Without going too much into detail, Cruise Control exposes a configurable set of rebalancing logic consisting of multiple `Goal`s, each of which is ran with its associated priority and balances on its associated resource.

Cruise Control continuously monitors the cluster’s metrics and automatically triggers a rebalance once it notices the metrics going outside of its defined acceptable thresholds.

Notably, Cruise Control also exposes API to allow you to easily add brokers to a cluster or remove brokers from a cluster. Because Kafka brokers are stateful (even with Tiered Storage), both of these operations require an operator to move replicas around.

Kafka Connect

If Kafka is to be the center of your event-driven architecture, you’re likely to:

- have a lot of systems whose data you’d like to get into Kafka (sources)

- have a lot of systems where you’d like to move data into from Kafka (sinks)

It’s likely that a lot of these systems are popular, widely-adopted ones ones - things like ElasticSearch, Snowflake, PostgreSQL, BigQuery, MySQL, etc.

Part of the Apache open-source project, Kafka Connect is a generic framework that allows you to integrate Kafka with other systems in a plug-and-play way that is reusable by the community.

The Kafka Connect runtime can be deployed in two modes:

- Standalone Mode — a single node, used mainly for development, testing, or small-scale data loading.

- Distributed Mode — a cluster of nodes that work in tandem to share the load of ingesting data.

Each node in Connect is called a Connect Worker. A worker is essentially a container that executes plugin code.

Community members develop battle-tested plugins that ensure fault tolerance, exactly-once-processing, ordering and other invariants that are cumbersome and time-consuming were you to have to develop from scratch. The name for such a plugin is a Connector — a ready to use library, deployed on a Connect Worker, for importing data into Kafka topics or exporting it to other external systems.

Workers heavily leverage internal Kafka topics to store their configuration, status, and checkpoint their progress (offsets).

They also leverage Kafka’s existing Consumer Group protocol to handle worker failures as well as propagate task assignments.

Users install plugins on the workers and use a REST API to configure/manage them. Such a plugin, called a Connector, can easily be deployed and configured to connect Kafka (a Kafka topic) with an external system.

The Connector code handles all the complex details around the data exchange so that users can focus on the simple configuration and integration. The code creates tasks for each worker to move data in parallel. These Connectors come in two flavors:

- Source Connector — used when sourcing data from another system (the source) and writing it to Kafka.

- Sink Connector — used when sourcing data from Kafka and writing it to another system (the sink).

In the diagram above we see two Source connectors running in two separate Connect clusters, each with its own workers, ingesting MongoDB/PostgreSQL data into Kafka.

A separate Connect cluster running Sink connectors then takes said data from Kafka and ingests it into Snowflake.

Kafka Streams

A stream processor is usually a client that reads the continuous streams of data from its input topics, performs some processing on this input, and produces a stream of data to output topics (or external services, databases, etc). In Kafka, It’s possible to do simple processing directly with the regular producer/consumer APIs; however, for more complex transformations like joining streams together, Kafka provides a integrated Streams API library.

Another part of the Apache open-source project, Kafka Streams is a client library that exposes a high-level API for processing, transforming and enriching data in real time.

This API is intended to be used within your own codebase — it’s not running on a broker. Unlike other stream processing frameworks, this one is native to Kafka and therefore doesn’t require a separate complex deployment strategy - it is deployed as a regular Kafka client, usually within your application.

It works similar to the consumer API and helps you scale out the stream processing work over multiple applications (similar to consumer groups).

Most notably, it supports exactly-once processing semantics when its input and output is a Kafka topic.

Optimizations / Future Work

While Kafka can seem like old software (it was first released in 2011!), the community is actively innovating on top of the protocol.

At this point, evidence points that the future will be everybody standardizing on the Kafka API and competing on the underlying implementation.

The current leader in the space is Confluent, founded by the original creators of Kafka, who have developed a cloud-native Kafka engine called Kora.

Notable competitors include RedPanda, which re-wrote Kafka in C++ and WarpStream, which innovated with a new architecture that leverages S3 heavily, completely avoiding replication and broker statefulness.

Vendors are largely competing in the cloud today - many offer a Kafka SaaS with varying levels of support. Some vendors offer a proper serverless SaaS experience by abstracting a lot of the details away, while others still require users to understand the details of the system and in some cases manage a large part of it themselves.

In summary, Kafka is mature, widely-adopted software that provides a rich set of features.

It is open source and boasts a very healthy community that continues to innovate stronger than ever after 13 years of development.