Let's Build Maker Cities for Maker People Around New Resources Like Bandwidth, Compute, and Atomically-Precise Manufacturing

Update: Larry Page wants a Google 2.0 that will build cities and airports, report says

TL;DR: There’s a lot of unused space in North America. Yet cities like San Francisco are becoming ever more expensive because of a bubble created by high tech jobs that seemingly can be done anywhere. Historically cities are built around resources that provide some service to humans. The age of infrastructure rising around physical resources is declining while the age of digital resource exploitation is rising. Cities are still valuable because they are amazing idea and problem solving machines. How about we create thousands of new Maker Cities in the vast emptiness that is North America and build them around digital resources like bandwidth, compute power, Atomically-Precise Manufacturing (AMP), and all things future and bright?

Observation Number One: There’s lots of empty space out there.

This summer my wife, myself, and two dogs took a 10,000 mile road trip from our home in near Santa Cruz California, across the US to visit the great province of Nova Scotia Canada, and many points around and in-between.

Hour after countless hour on the road created an overwhelmingly vivid thought in my mind: wow, there’s not much here. Land everywhere you look, but not many people.

Stats reinforce this feeling:

America is a vast, thinly populated country, with fewer than 90 people per square mile, the average American lives in a quite densely populated neighborhood, with more than 5000 people per square mile.

Here’s a 2010 population density map backing up the stats:

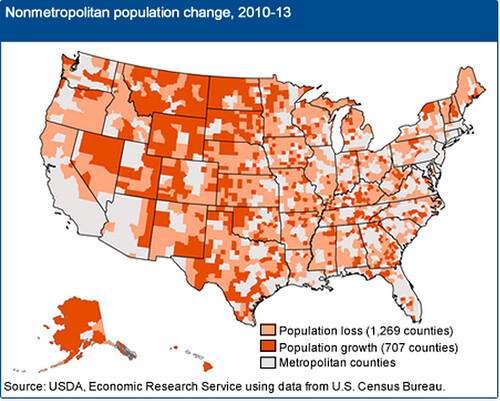

And we are seeing a depopulation with nearly two-thirds of rural U.S. counties having lost population since 2010:

Can’t at least some of that space be put to better use? Which brings us to the question of why would anyone move where there’s nothing? Which leads to...

Observation Number Two: Cities and infrastructure are built around resource reservoirs.

To understand the creation of cities, roads, bridges, ferries, railroads, canals, and other infrastructure in North America, you really need to understand the pattern of how resources have been exploited. This is a conclusion I came to while driving around playing tourist, because you actually get to learn why cities were built in the location they were built. And why they flourished sometime later after being established for another reason. And why they eventually die out.

Though it’s certainly not always the case that resources motivate city creation.

There are mystical reasons. Mexico City was founded in the location where an eagle was found perched on a nopal cactus with a snake in its beak. Salt Lake City was founded because Brigham Young had a vision that told him “this is the place.”

There are political reasons. The US capital was located in Washington DC as a political compromise between the North and South. Saint Petersburg was purpose built by Tsar Peter the Great as the imperial capital of Russia. Alexander the Great founded some twenty towns, often as a means of consolidating new mergers and acquisitions.

There are social reasons. From Why Do We Build Cities?:

The informal growth of Tell Brak [a settlement in Syria dating from around 6000 BCE] seems to suggest that, at their very beginnings, cities were founded because they provided a strong social network. This undoubtedly created economic and military power as early cities grew, but the original impetus was simply for people to gather in one place in order to improve their lives in some way (the researchers acknowledge that individual motivations were likely diverse). So Tell Brak illustrates at least one compelling argument for why we build large, impressive urban centers: we just like to be around each other.

But being the practical beings we are, it’s usually about resources, which means it’s about the money.

Resources are anything useful to humans: freshwater access, river transportation, harbors, ports, access to fisheries, a strong defensive position, fertile land, a crossroads, a ferry spot located on a narrow part of a river, where a train needs to stop for water, near minerals or mineral processing plants, near a temple, near a fort, near a trading post, near a financial center, near a market town, near military bases, near a river for hydropower, near hills for wind power, traveling distance from a town (every 20 miles if traveling on foot or 40 miles by coach), on trade routes, timber, oil, gas, coal, iron, and so on.

Here’s a North America Land Use & Resources Map from HowStuffWorks:

I couldn’t find a better map, but it does show some relationship between cities and resources. When I drive the back roads of California I’ve often thought most of the roads I was driving on are only there because trucks need access to farm products, timber, or some other resource like gold or other minerals. Otherwise who would go to the expense of building and maintaining a road?

This is an endlessly fascinating and deep topic, one we could spend a lot more time exploring, but I trust resources as a basis for city/town creation is relatively self-evident.

Observation Number Three: Programming can be done anywhere, there’s no need for everyone to move to San Francisco.

I don’t know where I heard it, I couldn’t find the quote, but it went something like:

Why is everyone moving to San Francisco and driving housing prices sky high when programmers can work anywhere?

That immediately struck me as a no duh moment. It is odd, isn’t it? Why does everyone want to work in the same place, especially when a red-hot job market has elevated rents to all-time highs in San Francisco and Oakland, and near all-time highs in San Jose? Rents were higher in San Jose during the previous tech boom and the fact that rents trail San Francisco tells you how much tech has moved away from San Jose and to San Francisco.

Many companies use distributed teams and they can work very well. InfoQ, for example, uses a completely distributed workforce, across several continents, and CEO Floyd Marinescu says they are quite happy with the results.

So why doesn’t everyone work remotely so they can live anywhere they want?

Because cities have a superpower.

Observation Number Four: Cities are idea machines in the same way that companies are idea machines.

I’m more of a country mouse than a city mouse, so admitting cities are a good idea does not come easy. I’m much more in tune with the romantic notion of programmers living free, yet connected over digital dendrites, forming part of large and multi-dimensional brain.

The fact is, cities work. William Meyer, associate professor of geography at Colgate University, makes a compelling case that:

Cities are much more efficient in the consumption of resources, notably energy, but also materials, also water, and also, of course, land, because of their higher densities.

Material efficiency is just part of the city advantage. Cities are also the best idea processing and problem solving machines ever invented. Certain network structures work better than others. You want people in a properly architected city for the same reason there’s a push to have workers colocated in the same building: increased productivity and creative output.

Someone who has done a lot of research in this area is Alex Pentland. You can read all about it in his wonderful book: Social Physics: How Good Ideas Spread—The Lessons from a New Science.

I have a hundred or so quotes from the book that range from mildly interesting to world view changing. I’ll only include a few here, but I’ll append the rest of the quotes at the end of the article for your perusal.

Money quotes from Social Physics:

The collective intelligence of a community comes from idea flow; we learn from the ideas that surround us, and others learn from us. Over time, a community with members who actively engage with each other creates a group with shared, integrated habits and beliefs. When the flow of ideas incorporates a constant stream of outside ideas as well, then the individuals in the community make better decisions than they could on their own

Consequently, the importance of packing people physically close to each other is still critical to promoting greater idea flow. Easy face-to-face access between individuals enhances exploration, engagement, and the rate at which new ideas are converted into behaviors. Thus, physical proximity remains perhaps the major factor in productivity and creative output.

In summary, people act like idea-processing machines combining individual thinking and social learning from the experiences of others. Success depends greatly on the quality of your exploration and that, in turn, relies on the diversity and independence of your information and idea sources.

If people are to work together efficiently, there needs to be what is called network constraint: repeated interactions between all of the members of the group—not just between a leader and the members, or between the members and the entire group (as at a group meeting).

Three simple patterns account[ed] for approximately 50 percent of the variation in performance across groups and tasks. The characteristics typical of the highest-performing groups included: 1) a large number of ideas: many very short contributions rather than a few long ones; 2) dense interactions: a continuous, overlapping cycling between making contributions and very short (less than one second) responsive comments (such as “good,” “that’s right,” “what?” etc.) that serve to validate or invalidate the ideas and build consensus; and 3) diversity of ideas: everyone within a group contributing ideas and reactions, with similar levels of turn taking among the participants

The important conclusion to take away from this Science paper is that groups have a collective intelligence that is mostly independent of the intelligence of the individual participants. This group problem-solving ability, which is greater than our individual abilities, emerges from the connections between the individuals. In particular, a pattern of interactions that supports the pooling of a diverse set of ideas from everyone, combined with an efficient winnowing process to establish a consensus, seems to form its core. Have we evolved to function better as group minds rather than as individuals?

In another company, the simplest way to increase workers’ productivity was to make the company’s lunch tables longer, thus forcing people who didn’t know each other to eat together

Social physics suggests that the reasons for creating cities are not that different from the reasons for creating work environments such as research parks or universities: We want to engineer the environment to enhance both exploration and engagement. While current digital technology makes remote interaction and collaboration extremely easy and convenient, we have seen that today’s digital technology is not as good at spreading new ideas as are face-to-face interactions.

We are smarter as a group. We work better together following certain rules of engagement. We work better when we interact personally with some frequency. Diversity helps prevent groupthink. The ability to constantly explore and bring in new ideas is crucial for an organization to keep innovating.

For all these reasons a properly structured city is the most innovative large scale organizational form. I know from talking to a lot of tech people who have moved to the Bay Area that the vibe here is different. There’s a vitality. Technology is all around you. Go to most any bar, restaurant, or coffee shop and you can hear people talking about technology. Meetups on all topics tech run continuously. Dozens of major corporations are headquartered here. VCs are here. Major conferences are here. When a tech person comes to Silicon Valley there's feeling that you are with your tribe. It's a true Maker City.

The Bay Area is a diverse, rich, inspirational and very productive environment. One that’s hard to duplicate, but since only so many people can live here and a city is the optimal organizational form, it makes sense to try, in the true startup spirit.

Conclusion: Create new digital resources around which new cities can be built.

So all this leads to the idea of creating new cities. Cities that are more affordable and open to settlement by digital explorers. There’s plenty of room.

These new cities would be built around digital resources. Provide oceans and fields and deposits and rivers of low cost bandwidth and processing power and they will come. Add in renewable power generation, smart recycling, smart grids, advanced green design to reduce water use, hydroponic food production, etc. and relatively low impact cities can be built.

The idea of bandwidth as an attractive resource has some legs. You hear about people and businesses considering moving to Kansas City just to have access to Google Fiber, for example, because all they need is bandwidth to work.

Nationwide it's estimated installing Google Fiber everywhere would cost a modest $11B. In comparison the US Interstate Highway System was calculated to have cost $425B in 2006 dollars. But the highway system, which was built as a way to transfer material resources across a nation, was constructed when the US could still do big things. The Manhattan Project cost $55B in today's dollars. And the failed F-35 fighter aircraft cost $7.4B.

Money isn't the problem. Leadership is the problem, so smaller regions have stepped up to fill the vision chasm. Chattanooga battled Big Cable, winning the right to install a 1 gigabit per second fiber network in their own community, and the result is driving a "driving a tech boom." So bandwidth is an attractive resource in the new digital resource economy.

What would a Maker City look like? I don't want to say, I’m leery of any top down methodologies for building cities.

William Meyer has some ideas about the organization of cities in his book Social Physics:

But what if we could have both the high levels of social engagement characteristic of traditional villages (and hence their lower crime rate), and the high levels of exploration characteristic of sophisticated business and cultural areas (and hence their greater creative output)? We want to increase engagement in the residential areas, which will lead to stronger norms of behavior, but not increase the amount of exploration for everyone, since that would lead to more crime along with

The failure of most city zoning is that if cities segregate by function, then exactly the wrong change in the structures of social ties occurs: Engagement decreases locally (if an area is all just apartment blocks, people rarely get out and meet each other), and exploration increases (since people have to go elsewhere to do anything), and as a consequence the social fabric of the neighborhood is pulled apart.

Jane Jacobs argued, a healthy city has complete, connected neighborhoods.

This goal suggests packing as many people as possible into a central city with very efficient and cheap transportation.

The result is that the center of Zurich has the dense flows of new ideas necessary for a flourishing work and cultural environment, but the surrounding villages also have the strong social engagement required to keep them healthy.

Designing a city for fast, flat-rate transportation that promotes both village-style neighborhoods and central big business and cultural areas may be the simplest and cheapest way to both improve poor neighborhoods and increase overall productivity.

Paris, London, New York, and Boston all were built from small, walking-sized neighborhoods that were later linked by subways and light rail.

So not a utopia, which literally means "no place." Not a libertopia, that has some political agenda. But a real growing city that has a fresh start. Where services like Uber and Google’s robotic cars can innovate in a supportive environment. Where the city is instrumented so as to support new ways of interacting socially and being controlled smartly. Where a cheap machine-to-machine network can make IoT a reality. Where drone delivery isn’t just a fanciful idea. In short, Maker Cities populated by Maker People. High octane innovation engines.

Perhaps Maker City Starters can be used to finance the creation of different approaches to Maker Cities in different regions? All American colonies were privately financed. So it's not a completely crazy idea.

Related Articles

The Role of Geography in Development by Paul Krugman

The Geography of the New Economy by R. D. Norton

Origin of Cities by Sander van der Leeuw

Was the "urban revolution" really a revolution ? by Michael E. Smith

The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires by Tim Wu

Radical Abundance: How a Revolution in Nanotechnology Will Change Civilization by K. Eric Drexler

Nature's Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West - Chicago's rise had to do with its becoming a railroad hub, which was driven not by location (aside from being roughly in the middle of the country), but rather by boosterism. Eastern investors invested in whichever city sounded most likely to succeed and Chicago gained more traction than any of its rivals.

What are some examples of cities that were founded in illogical places? - great thread on Metafilter.

States with Faster Internet Access Have Smarter People

The Environmental Advantages of Cities By William B. Meyer

Sandy Pentland: "Social Physics: How Good Ideas Spread" | Talks at Google

How does a city/town actually get started? Are new cities still being created in the US?

Old World, New Tech - Europe Remains Ahead of U.S. in Creating Smart Cities

Government For The People, By The People, In the 21st Century by Tim O'Reilly

Has the ideas machine broken down?

Nationwide Google Fiber would cost $11B over five years, probably will never happen

National Broadband Plan (United States)

Grand Canal - Irigation canals greened Mesopotamia and midwifed the first great civilizations; state-dug canals were the early arteries of England's Industrial Revolution

More Thought Provoking Quotes from Social Physics

Social physics is a quantitative social science that describes reliable, mathematical connections between information and idea flow on the one hand and people’s behavior on the other. Social physics helps us understand how ideas flow from person to person through the mechanism of social learning and how this flow of ideas ends up shaping the norms, productivity, and creative output of our companies, cities, and societies. It enables us to predict the productivity of small groups, of departments within companies, and even of entire cities. It also helps us tune communication networks so that we can reliably make better decisions and become more productive. The key insights obtained with social physics all have to do with the flow of ideas between people. This flow of ideas can be seen in the pattern of telephone calls or social media messaging, of course, but also by assessing how much time people spend together and whether they go to the same places and have similar experiences. As we will see, flows of ideas are central to understanding society not only because timely information is critical to efficient systems but, more important, because the spread and combination of new ideas is what drives behavior change and innovation. This focus on the flow of ideas is why I chose the name “social physics.” Just as the goal of traditional physics is to understand how the flow of energy translates into changes in motion, social physics seeks to understand how the flow of ideas and information translates into changes in behavior.

Put another way, social physics is about how human behavior is driven by the exchange of ideas—how people cooperate to discover, select, and learn strategies and coordinate their actions—rather than how markets are driven by the exchange of money.

Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty, because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things.

Focus on the flow of ideas rather than the flow of wealth since the flow of ideas is the source of both cultural norms and innovation.

The largest factor in predicting group intelligence was the equality of conversational turn taking; groups where a few people dominated the conversation were less collectively intelligent than those with a more equal distribution of conversational turn taking

Rather than focusing on individual thoughts and emotions, social physics focuses on social learning as the major driver of habits and norms. A fundamental assumption is that learning from examples of other people’s behavior (and the relevant contextual features) is a major and likely dominant mechanism of behavior change in humans.

One disturbing implication of these findings is that our hyperconnected world may be moving toward a state in which there is too much idea flow. In a world of echo chambers, fads and panics are the norm, and it is much harder to make good decisions.

As a consequence of these shared habits, human communities can develop a sort of collective intelligence that is greater than the members’ individual intelligence. Engagement with and learning from others, along with the mutual sharing and vetting of ideas, generate the collective intelligence.

I believe that we can we think of each stream of ideas as a swarm or collective intelligence, flowing through time, with all the humans in it learning from each other’s experiences in order to jointly discover the patterns of preferences and habits of action that best suit the surrounding physical and social environment.

Average performers thought teamwork meant doing their part on the team. Star performers, however, saw things differently: They pushed everyone on the team toward joint ownership of goal setting, group commitments, work activities, schedules, and group accomplishments. That is, star performers promoted synchronized, uniform idea flow within the team by making everyone feel a part of it, and tried to reach a sufficient consensus so that everyone would willingly go along with new ideas.

Groups of people, as well as communities, also have a collective intelligence that is different from the individual intelligence of each group member. Moreover, this group intelligence is about as important a factor in predicting group performance as IQ is in predicting individual performance.

The largest factor in predicting group intelligence was the equality of conversational turn taking; groups where a few people dominated the conversation were less collectively intelligent than those with a more equal distribution of conversational turn taking.

It appears that being in the loop allows employees to learn tricks of the trade—the kind of tacit, detailed experience that separates novices from experts—and is what keeps the idea machine efficiently ticking along.

Put another way, the process of oscillation between exploration and engagement appears to increase creative output by building up a more diverse store of experiences that can be drawn on as examples

The result of this research is a simple mathematical equation that describes how people tend to have lots of social ties to people who live nearby and increasingly fewer ties with people who are farther and farther away.

If we looked at cities with greater than average rates of exploration in the credit card data, we found that in subsequent years they had a higher GDP, a larger population, and a greater variety of stores and restaurants. It makes sense that more exploration, which results in a greater number of interactions between current norms and new ideas, would be a driver of innovative behavior

It seems that not only does exploration result in growing more creative and richer cities, but the process is self-reinforcing. Greater exploration begets greater opportunities for exploration.

Instead, people’s exploration is open-ended, and they seem to never stop sampling new stores and services.

One way to interpret all of these findings is that the more people want to learn from a particular peer group, i.e., the more they want to fit in, then the more time they spend around them. Which is why you need divergence.

As the work of Stanley Milgram on social conformity demonstrated, when our peers are all doing the same thing, be it gaining or losing weight, or even doing something outrageous such as doling out electric shocks, the uniformity of the example behaviors around us strongly influences both unconscious habits and conscious decisions.

We can resist the flow if we try, and even choose to row to another stream, but most of our behavior is shaped by the ideas we are exposed to. The idea flow within these streams binds us together into a sort of collective intelligence, one comprised of the shared learning of our peers.

We are now coming to realize that human behavior is determined as much by social context as by rational thinking or individual desires. Rationality, as the term is used by economists, means that we know what we want and act to get it. But I think that my research shows that both people’s desires and their decisions about how to act are often, and perhaps typically, dominated by social network effects.

The point is not just that it’s possible to get lots of people to work. Rather, the point is that it’s possible to get people to build an organization that does the work. That is why we rewarded people both for finding balloons and for recruiting people to help search. We rewarded people roughly equally for these two tasks, because building the network was just as important as the actual work of searching

Exploration among groups improves both productivity and creative output.

The result of this research is a simple mathematical equation that describes how people tend to have lots of social ties to people who live nearby and increasingly fewer ties with people who are farther and farther away.

It seems that not only does exploration result in growing more creative and richer cities, but the process is self-reinforcing. Greater exploration begets greater opportunities for exploration.

Instead, people’s exploration is open-ended, and they seem to never stop sampling new stores and services.

Our data show that people are more than simple economic creatures. They do explore in order to find better deals, but they also explore from a sense of curiosity. This tendency is most evident in the wealthiest segments of society. With these people, the rate at which they explore new stores and restaurants is unconnected to the rate at which they switch where and what they buy.

This suggests that when people have abundant resources, it is their curiosity and social motivations that drive their exploratory behavior and not the desire to find cheaper prices or a better product.

This goal suggests packing as many people as possible into a central city with very efficient and cheap transportation. Ideally

The goal is to get maximum exploration in the economic and cultural centers, along with maximum engagement in the towns.

It is not simply the brightest who have the best ideas; it is those who are best at harvesting ideas from others. It is not only the most determined who drive change; it is those who most fully engage with like-minded people. And it is not wealth or prestige that best motivates people; it is respect and help from peers

This is just what I see when I look at the most productive people in the world: They are continually engaging with others in order to harvest new ideas, and this exploratory behavior creates better idea flow.

The effects of exposure to peer behaviors are roughly the same size as the influence of genes on behavior or IQ on academic performance. Moreover, in each case it appears that exposure to surrounding peer behaviors is the largest single factor driving idea flow.

There is growing evidence that the power of engagement—direct, strong, positive interactions between people—is vital to promoting trustworthy, cooperative behavior.

I have found that interaction patterns within them typically account for almost half of all the performance variation between high- and low-performing groups.

Exploration is how much the members of a group bring in new ideas from outside; that in turn predicts both innovation and creative output.

The social physics view of organizations focuses on patterns of interaction acting as a kind of “idea machine” to carry out the necessary tasks of idea discovery, integration, and decision making.

It seems that not only does exploration result in growing more creative and richer cities, but the process is self-reinforcing. Greater exploration begets greater opportunities for exploration.

The mathematics of how ideas spread and convert into new behaviors quite precisely accounts for the empirically observed growth of cities across multiple features and different geographies. There is no need to appeal to assumptions about social hierarchies, specialization, or other special social constructs in order to explain how GDP, research and development, and crime grow with increasing city population.