How can we Build Better Complex Systems? Containers, Microservices, and Continuous Delivery.

We must be able to create better complex software systems. That’s that message from Mary Poppendieck in a wonderful far ranging talk she gave at the Craft Conference: New New Software Development Game: Containers, Micro Services.

The driving insight is complexity grows nonlinearly with size. The type of system doesn’t really matter, but we know software size will continue to grow so software complexity will continue to grow even faster.

What can we do about it? The running themes are lowering friction and limiting risk:

Lower friction. This allows change to happen faster. Methods: dump the centralizing database; adopt microservices; use containers; better organize teams.

Limit risk. Risk is inherent in complex systems. Methods: PACT testing; continuous delivery.

Some key points:

When does software really grow? When smart people can do their own thing without worrying about their impact on others. This argues for building federated systems that ensure isolation, which argues for using microservices and containers.

Microservices usually grow successfully from monoliths. In creating a monolith developers learn how to properly partition a system.

Continuous delivery both lowers friction and lowers risk. In a complex system if you want stability, if you want security, if you want reliability, if you want safety then you must have lots of little deployments.

Every member of a team is aware of everything. That's what makes a winning team. Good situational awareness.

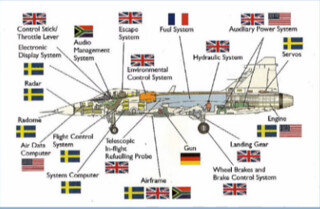

The highlight of the talk for me was the section on the amazing design of the Swedish Gripen Fighter Jet. Talks on microservices tend to be highly abstract. The fun of software is in the building. Talk about parts can be so nebulous. With the Gripen the federated design of the jet as a System of Systems becomes glaringly concrete and real. If you can replace your guns, radar system, and virtually any other component without impacting the rest of the system, that’s something! Mary really brings this part of the talk home. Don’t miss it.

It’s a very rich and nuanced talk, there’s a lot history and context given, so I can’t capture all the details, watching the video is well worth the effort. Having said that, here’s my gloss on the talk...

Hardware Scales by Abstraction and Miniaturization

Software hasn’t come very far in the last 40 years, while hardware has come a long way:

CPUs, algorithms, interfaces, etc. have been abstracted into single chips and those chips have been miniaturized.

Chips are added to boards, boards are attached to motherboards, and the motherboard are then abstracted and reduced.

A motherboard is a bunch of sockets and each socket takes some sort of abstraction. Like a platform. There’s memory, CPU, etc. Every socket has a thing you can plug into it. You can fit any kind of compatible memory into the socket.

The process is repeated over and over again.

But software does not scale the same way as hardware.

Software Scales by Federation & Wide Participation

When does software really grow? When smart people can do their own thing without worrying about their impact on others.

We’ve seen this pattern of flourishing in both the growth of the web and the cloud.

In 1989 Tim Berners-Lee created his idea of the hyperlink, which spawned the Mosaic web browser in 1993. All of a sudden we had an explosion of software distributed all over the world.

The web scaled because each node could do their own processing, completely federated from everyone else. Each node could do their own thing. What one node does doesn’t matter to any other node. There’s nothing a node can do to effect any other node. Nodes are isolated from each other.

The cloud repeats this pattern. We’ve seen another explosion of software with the cloud. What is happening is an environment is being created where individuals, or teams, or companies, can do their own thing without impacting others.

This is how we’ve scaled software in the past and is how we can scale software in the future.

Monolithic Architectures Fail by Increasing Friction through Centralized Databases

The centralized database becomes a massive coupling mechanism. Every single thing in an entire system is locked together because each component must use the database to manage state.

If we need to decouple as we did on the internet and federate so everyone can make changes independently of each other, then the database can’t be system wide.

Centralized databases are a high friction architecture.

Microservices Succeed by Reducing Friction

Microservices remove the database as a coupling device. The scary and counter-intuitive idea is that each service has its own database.

Microservices gives each team and independent ability to change what they do.

Lowering friction allows change to happen faster.

A microservice does one thing well.

A microservices is independently deployable. A federated architecture. Services can be deployed independently of any other service, with the constraint that they don’t break their service contract.

A micro service is created by a small team that contains all the skills necessary to build, deploy, and manage the service. The team has end-to-end responsibility for the service.

Practices: no central databases; extensive automation and monitoring; consumer driven contract testing; smart versioning services; canary releasing.

Microservices Increase Risk

-

While microservices certainly lower friction they also increase risk from wiring hell and bad partitioning.

-

There’s always the possibility of creating a wiring hell between services.

-

Objects promised much the same benefits of microservices. Objects eventually become so interconnected that they lost their benefits.

-

-

To mitigate the wiring risk with microservices:

-

Bounded context. Every microservice should match something in the real world. That it’s natural.

-

Consolidator services to make sure the underlying services behave themselves.

-

Discipline. There’s no path to a service except through the interface.

-

Change awareness. Teams have to watch out for the impact of any change.

-

-

Microservices usually grow successfully from monoliths.

-

Only when they really understood their domain did they switch to microservices.

-

Refactoring in a monolith is easy, it’s not easy in a microservice. If you don’t get the structure right it’s really hard to refactor.

-

Success stories come from companies that started with monoliths because they were able to learn their domain and make good decisions about microservice partitions.

-

Example of Federation in a System of Systems Design with the Swedish Gripen Fighter Jet

Amazing visionary systems engineering which created an architecture that made for a much lower cost of development is revealed in the fascinating story of the design of the Swedish Gripen fighter jet.

Sweden parks their jets in cul-de-sacs where they are hidden in the trees. They land on roads that are half a kilometer long. They are serviced by a truck with a half dozen conscripts and one engineer in 30 minutes.

Focus was to continually reduce operating costs. The Gripen costs $4,700 per hour to operate. The F35 costs $31,000 per hour to operate. Each generation of Gripen became cheaper to operate.

Design goals: high reliability, low cost, nimble performance.

What they came up with was the Gripen Integrated Federated Architecture. Or a smartphone architecture. There’s an avionics platform and a bunch of apps. The apps are things like environmental control system, hydraulics system, auxiliary power, etc.

Lots of people have built radar systems and gun systems. If you do the architecture right you can just buy these systems. In a true federated architecture the gun, for example, could have its own changes without impacting the rest of the system.

Even though this a safety critical system and there are a lot of regulations surrounding airplanes, they were still able to design it so the avionics platform was truly separated out so that anyone of the major subcomponents can be swapped out without messing up the avionics system.

They allow true separate insertion of any component from any country and the avionics platform does not have to be recertified.

They major upgrades of the Gripen platform and the Android platform have occurred at about the same rate. What they have is rapid avionics platform development and independent federated components.

Instead of having a separate computer for each component, which they can’t do because of weight restrictions, what they’ve done is create a hardened container inside a single computer that guarantees no system in the container can have any impact on any other system in the container. None of them can consume all the resource in the container. When you can prove that you can have architecture that allows the components to be controlled by the same hardware you can have a completely federated architecture while staying within in weight limitations.

Containers Decrease Friction, but Not Risk

Friction slows things down.

Containers lower friction. Ships before containers had every product individually packed by longshoremen. In the 1970s there was a move to container ships. Much lower friction now and it created an economic revolution.

Software containers also lower friction. Can build once and run anywhere because the environment will be consistent. Different systems are isolated so there’s federation. They also increase server utilization and reduce costs.

Containers are not about limiting risk.

Continuous Delivery Lowers Friction and Lowers Risk

How do you know when you deploy your microservice that a microservice you use that was just deployed five minutes ago didn’t break anything? It’s not an easy problem.

End-to-end testing doesn’t solve the problem because code is changing too fast. And with end-to-end testing you’ve lost your independent deployment mechanism and it slows you down a lot.

The goal is to lower risk without increasing friction, but here’s a tension between the two. We do not want to abandon services, we want to increase the chance of a service deploying correctly.

So one way is to run a set of tests to verify contracts before deploying. They should run quickly and give some satisfaction that your deployed code will work with existing services. PACT: Enables consumer driven contract testing, providing a mock service and DSL for the consumer project, and interaction playback and verification for the service provider project.

The problem is when dealing with a complex system you can’t test it and expect that you know how it will work. Any time you make a massive change to a complex system you don’t know how it’s going to respond. No matter how hard you try there will be surprises.

So don’t try. Poke it. The only way large complex systems can ever remain stable is to continually poke it and see how it responds. Note: I’m not exactly sure what poke means here. It wasn’t clear. Is it continuous testing? Is it continuous deployment? Is it Netflix style chaos monkeys?

The idea that lots of little deployments is dangerous is wrong. The only thing that’s a good idea with a complex system is lots of little deployments.

If you want stability, if you want security, if you want reliability, if you want safety then you must have lots of little deployments.

Continuous deployments is where you need to be with any large scale complex system.

Organization

What makes a winning team? Every member of a team is aware of everything. There’s good situational awareness.

Create a shared goal like delighting customers.

No one succeeds unless everyone succeeds.

Create situational awareness by making the world visible through monitoring.

Regulatory Fit Theory. Two kinds of people: safety-focused (prevent failure, is it safe?); aspirational focus (create gains, do it!). Need both kinds of people on a team to balance each other out.