Engineering dependability and fault tolerance in a distributed system

This is a guest post by Paddy Byers, Co-founder and CTO at Ably, a realtime data delivery platform. You can view the original article on Ably's blog.

Users need to know that they can depend on the service that is provided to them. In practice, because from time to time individual elements will inevitably fail, this means you have to be able to continue in spite of those failures.

In this article, we discuss the concepts of dependability and fault tolerance in detail and explain how the Ably platform is designed with fault tolerant approaches to uphold its dependability guarantees.

As a basis for that discussion, first some definitions:

Dependability

AvailabilityReliability

Availability

availablestatistically independent failures

Reliability

conforms to its specificationcontinue to work as its users expect

Fault tolerance

dependable

Fault tolerant systems tolerate faults: they’re designed to mitigate the impact of adverse circumstances and ensure the system remains dependable to the end-user. Fault-tolerance techniques can be used to improve both availability and reliability.

Availability can be loosely thought of as the assurance of uptime; reliability can be thought of as the quality of that uptime — that is, assurance that functionality and user experience and preserved as effectively as possible in spite of adversity.

If the service isn’t available to be used at the time it is needed, that’s a shortfall in availability. If the service is available, but deviates from its expected behavior when you use it, that’s a shortfall in reliability. Fault tolerant design approaches address these shortfalls to provide continuity both to business and to the user experience.

Availability, reliability, and state

In most cases, the primary basis for fault tolerant design is redundancy: having more than the minimum number of components or capacity required to deliver service. The key questions relate to what form that redundancy takes and how it is managed.

In the physical world there is classically a distinction between

- availability situations, where it is acceptable to stop a service and then resume it, such as stopping to change a car tire; and

- reliability situations, where continuity of service is essential, with redundant elements continuously in-service, such as with airplane engines.

The nature of the continuity requirement impacts the way that redundant capacity needs to be provided.

In the context of distributed systems, at Ably we think of an analogous distinction between components that are stateless and those that are stateful, respectively.

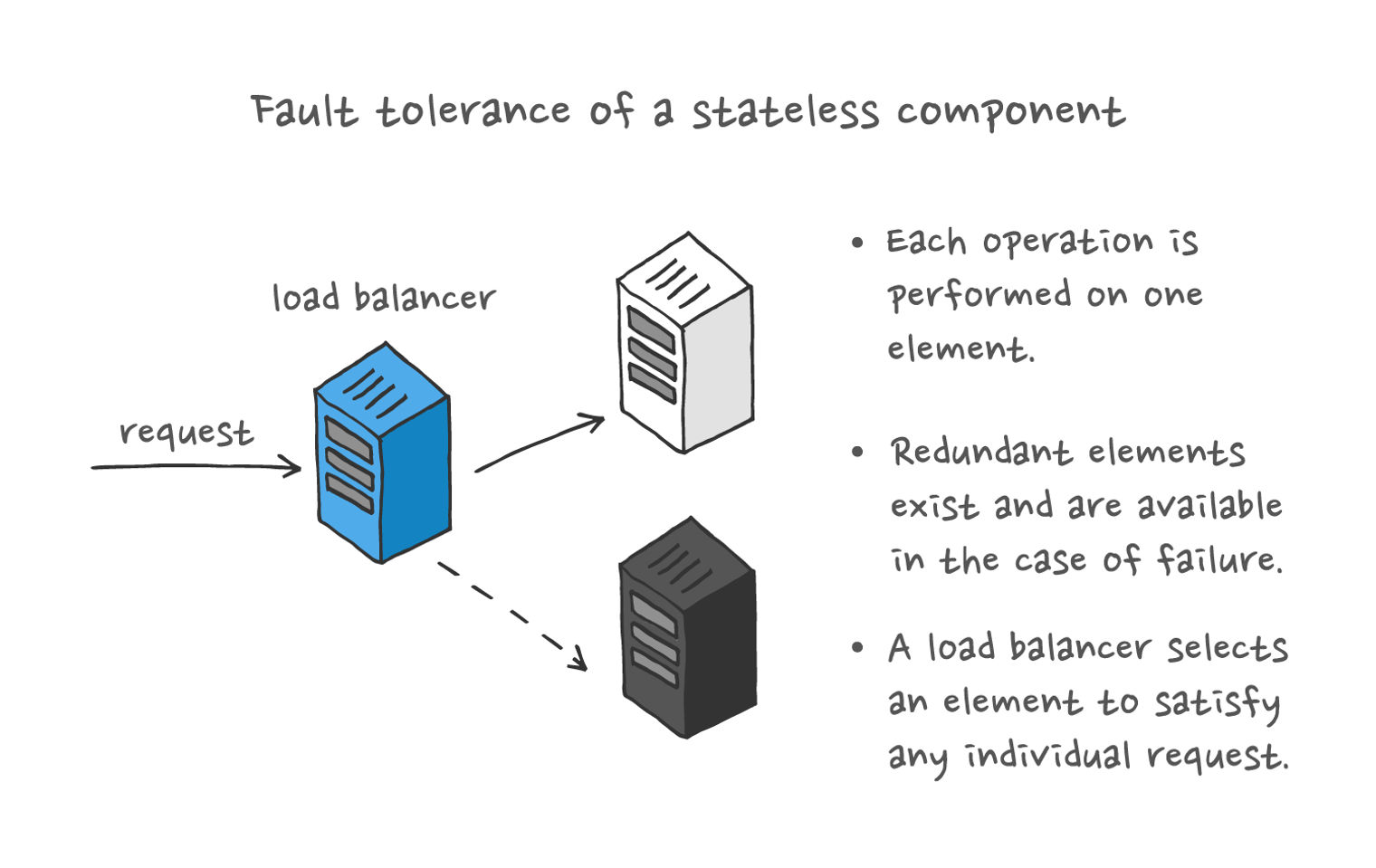

Stateless components fulfil their function without any dependency on long-lived state. Each invocation of service can be performed independently of any previous invocation. Fault tolerant design for these components is comparatively straightforward: have sufficient resources available so that any individual invocation can be handled even if some of the resources have failed.

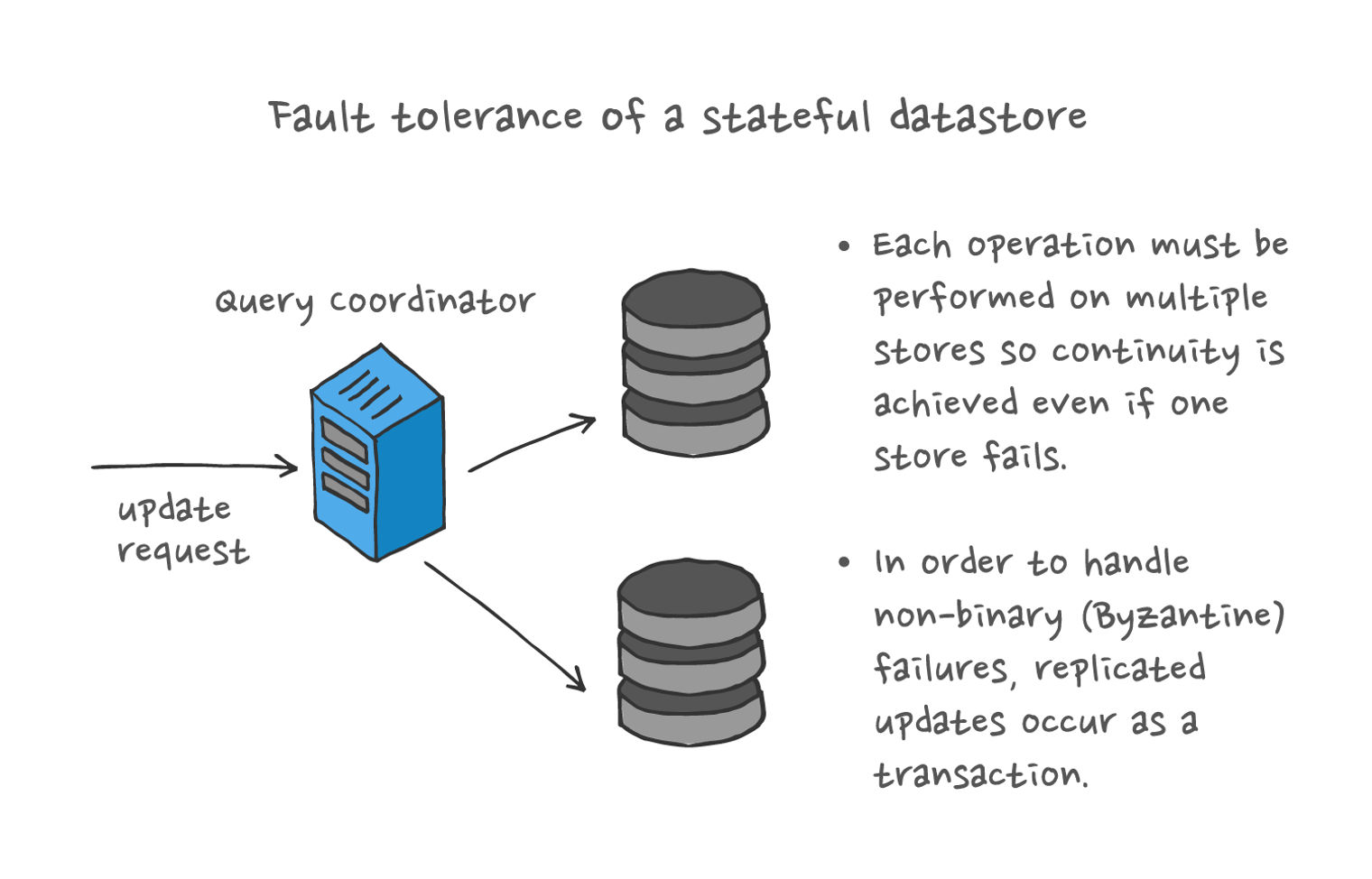

Stateful components have an intrinsic dependency on state to provide service. Having state implicitly links an invocation of the service to past and future invocations. The essence of fault tolerance for these components is, as with an airplane's engines, about being able to provide continuity of operation — specifically, continuity of the state that the service depends on. This ensures reliability.

In the remainder of this article we will give examples of each of these situations and explain the engineering challenges encountered in achieving fault tolerance in practice.

Treating failure as a matter of course

Fault tolerant designs treat failures as routine. In large-scale systems, the assumption has to be that component failures will happen sooner or later. Any individual failure must be assumed as imminent and, collectively, component failures must be expected to be occurring continuously.

By contrast with the physical world, failures in digital systems are typically non-binary. The classical measures of component reliability (e.g. Mean Time Between Failures, or MTBF) do not apply; services degrade along a gradient of failure. Byzantine faults are a classic example.

For example, a system component might work intermittently, or produce misleading output. Or you might be dependent on external partners who don’t notify you of a failure until it becomes serious on their end, making your work more difficult.

Being tolerant to non-binary failures requires a lot of thought, engineering and, sometimes, human intervention. Each potential failure must be identified and classified, and must then be capable of being remediated rapidly, or avoided through extensive testing and robust design decisions. The core challenge of designing fault-tolerant systems is understanding the nature of failures and how they can be detected and remediated, especially when partial or intermittent, to continue to provide the service as effectively as possible for users.

Stateless services

Service layers that are stateless do not have a primary requirement for continuity of service for any individual component. The availability of resources directly translates into availability of the layer as a whole. Having access to extra resources whose failures are statistically independent is key to keeping the system going. Wherever possible, layers are designed to be stateless as a key enabler not only of availability, but also of scalability.

For stateless objects, it suffices to have multiple and independently available components to continue to provide service. Without state, durability of any single component is not a concern.

However, simply having extra resources is not enough: you also have to use them effectively. You have to have a way of detecting resource availability, and to load-balance among redundant resources.

As such, the questions that you have to answer are:

- How do you survive different kinds of failure?

- What level of redundancy is possible?

- What is the resource and performance cost of maintaining those levels of redundancy?

- What is the operational cost of managing those levels of redundancy?

The consequent trade-offs are among the following:

- Customer requirements for achieving high availability

- Business operational cost

- Real world engineering practicality of actually making it possible

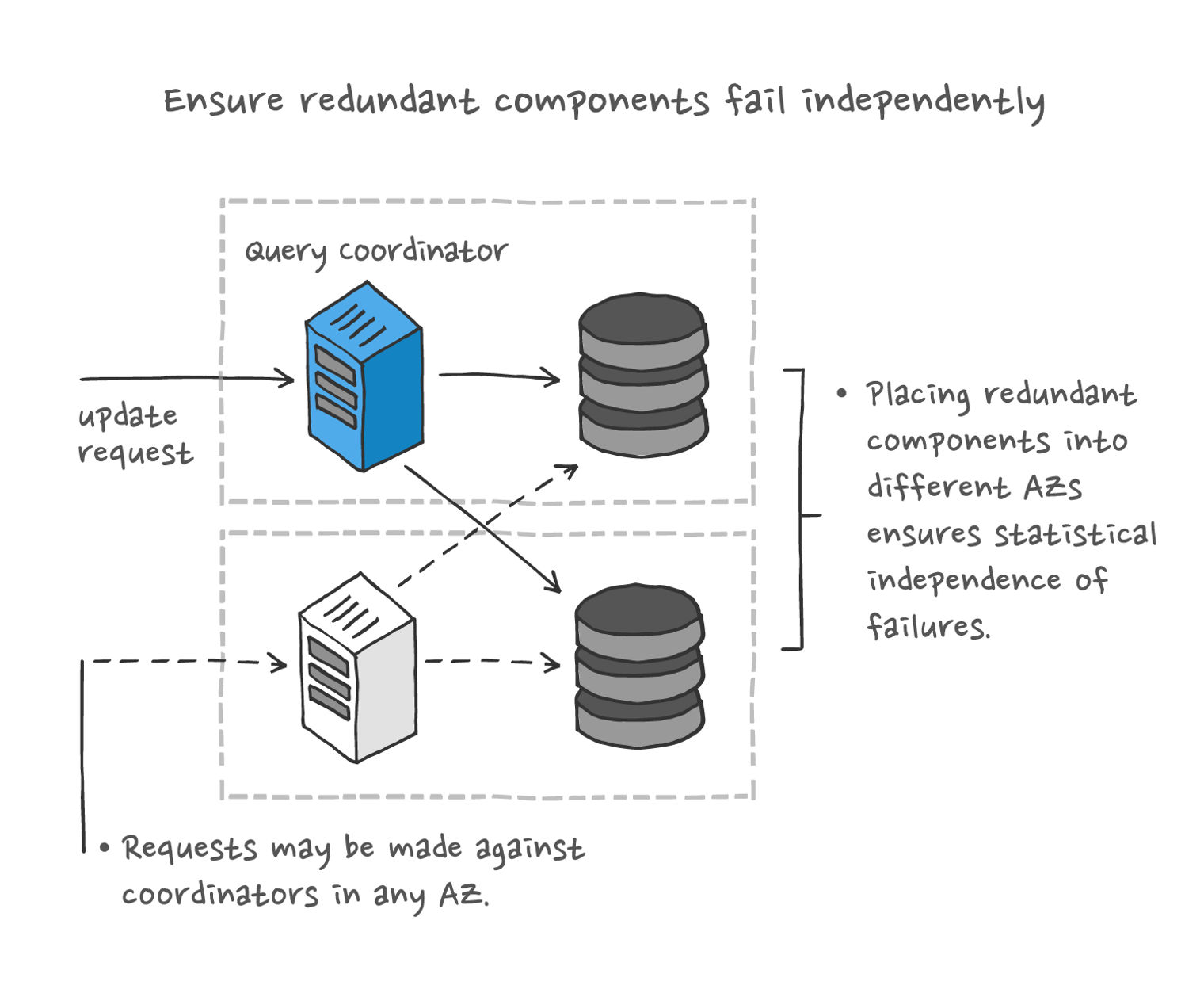

Redundant components, and in turn their dependencies, need to be engineered, configured and operated in a way that ensures that any failures are statistically independent. The simple math is: statistically independent failures render your chances of a catastrophic failure exponentially lower as you increase the level of redundancy. If the failures are set up to occur in statistical silos, then there is no cumulative effect, and you decrease the likelihood of complete failure by a whole order of magnitude with each additional redundant resource.

At Ably, to increase statistical independence of failures, we place/distribute capacity in multiple availability zones and in multiple regions. Offering service from multiple availability zones within the same region is relatively simple: AWS enables this with very little effort. Availability zones generally have a good track record of failing independently, so this step by itself enables the existence of sufficient redundancy to support very high levels of availability.

However, this isn’t the whole story. It isn’t sufficient to rely on any specific region for multiple reasons – sometimes multiple availability zones (AZs) do fail at the same time; sometimes there might be local connectivity issues making the region unreachable; and sometimes there might simply be capacity limitations in a region that prevent all services from being supportable there. As a result, we also promote service availability by providing service in multiple regions. This is the ultimate way of ensuring statistical independence of failures.

Establishing redundancy that spans multiple regions is not as straightforward as supporting multiple AZs. For example, it doesn’t make sense simply to have a load balancer distributing requests among regions; the load balancer itself exists in some region and could become unavailable.

Instead, we use a combination of measures to ensure that client requests can at all times be routed to a region that is believed to be healthy and have service available. This routing will preferably be to the nearest region, but routing to non-local regions must be possible when the nearest region is unable to provide service.

Stateful services

At Ably, reliability means business continuity of stateful services, and it is a substantially more complicated problem to solve than just availability.

Stateful services have an intrinsic dependency on state that survives each individual invocation of service. Continuity of that state translates into correctness of the service provided by the layer as a whole. That requirement for continuity means that fault tolerance for these services is achieved by thinking of them in classic reliability terms. Redundancy needs to be continuously in use, in order for the state not to become lost in the case of failure. Fault detection and remediation needs to address the possible Byzantine failure modes via consensus formation mechanisms.

The most simplistic analogy is with airplane safety. An airplane crash is catastrophic because you – and your state – are on a specific airplane; it is that airplane which must provide continuous service. If it fails to do so, state is lost and you are afforded no opportunity to continue by migrating to a different airplane.

With anything that relies on state, when an alternate resource is selected, the requirement is to be able to carry on with the new resource where the previous resource left off. State is thus a requirement, and in those cases availability alone is insufficient.

At Ably, we provision enough reserve capacity for stateless resources to support all of our customers’ availability requirements. However, for stateful resources, not only do we need redundant resources, but also explicit mechanisms to make use of that redundancy, in order to support our service guarantees of functional continuity.

For example, if processing for a particular channel is taking place on a particular instance within the cluster, and that instance fails (forcing that channel role to move), mechanisms must be in place to ensure that things can continue.

This operates at several levels. At one level, a mechanism must exist to ensure that that channel’s processing is reassigned to a different, healthy, resource. At another level, there needs to be assurance that the reassigned resource continues at exactly the point that processing was halted in the previous location. Further, each of these mechanisms is itself implemented and operated with a level of redundancy to meet the overall assurance requirements for the service.

The effectiveness of these continuity mechanisms directly translates into the behavior, and assurance of that behavior, at the service provision boundary. Taking one specific issue in the scenario above: for any given message, you need to know with certainty whether or not processing for that message has been completed.

When a client submits a message to Ably for publication, and the service accepts the message for publication, it acknowledges that attempt as successful or unsuccessful. At this point, the principal availability question is:

What fraction of the time does the service accept (and then process) the message, versus rejecting it?

The minimum aim in this case is four, five, or even six 9s.

If you attempt to publish and we let you know we weren’t able to do that, then that’s merely an availability shortcoming. It’s not great, but you end up with an awareness of the situation.

However, if we respond with success — "yes, we've received your message" — but then we fail to do all the onward processing of it, then that's a different kind of failure. That's a failure to uphold our functional service guarantee. That’s a reliability shortcoming, and it’s a far more complicated problem to solve in a distributed system — there is significant engineering effort and complexity devoted to meeting this requirement.

Architectural approaches to achieve reliability

The following are two illustrations of the architectural approaches we adopt at Ably to make optimum use of redundancy within our message processing core.

Stateful role placement

In general, horizontal scalability is achieved by distributing work across a scalable cluster of processing resources. As far as entities that perform stateless processing are concerned, they can be distributed across available resources with few constraints on their placement: the location of any given operation can be decided based on load balancing, proximity, or other optimization considerations.

Meanwhile, in the case of stateful operations, the placement of processing roles must take their stateful nature into account such that, for example, all concerned entities can agree on the specific location of any given role.

A specific example is channel message processing: whenever a channel is active it gets assigned a resource that processes it. Being a stateful process, it is possible to achieve greater performance: we know more about the message at the time of processing, so we don’t have to look it up — we can just process it and send it on.

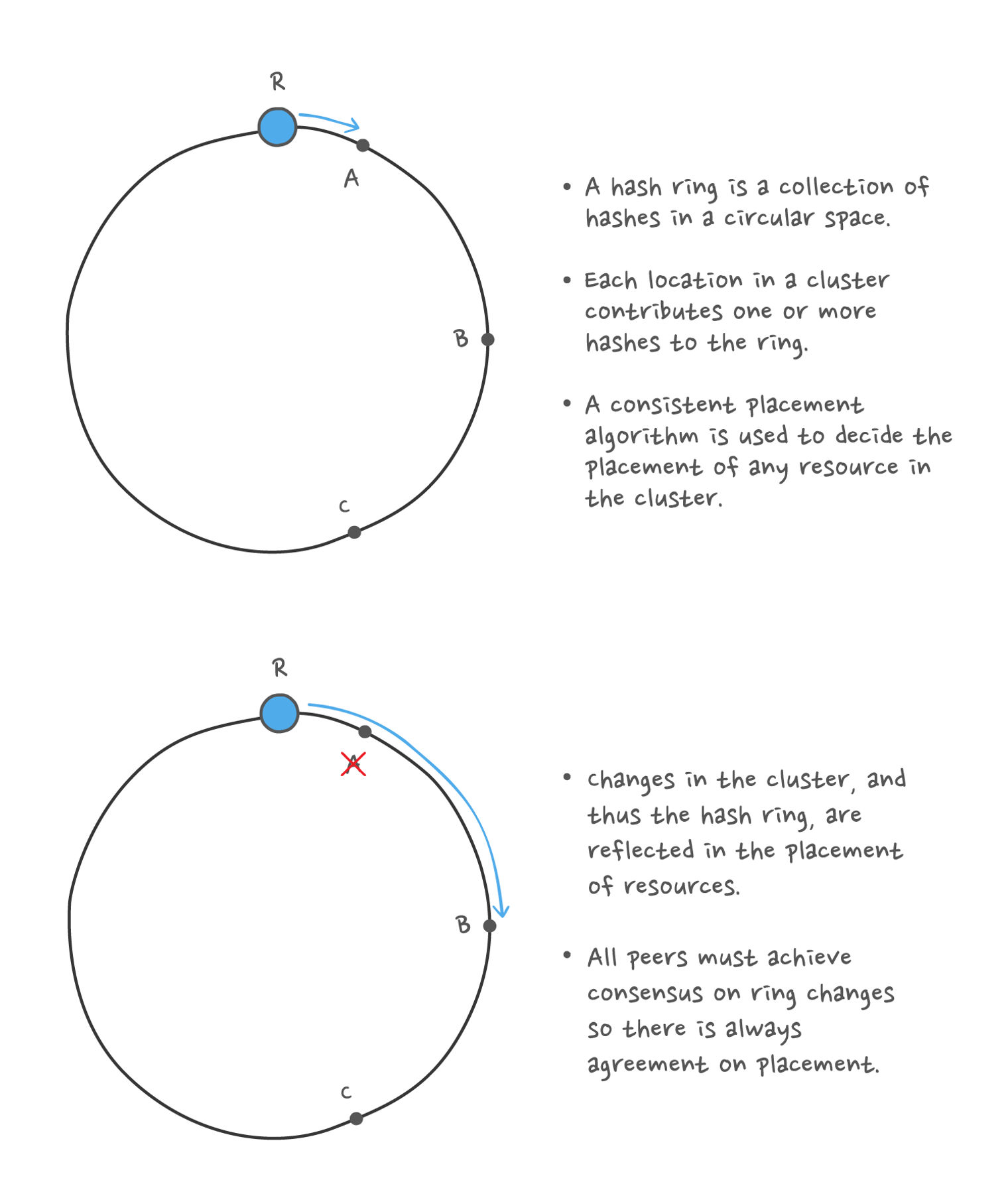

In order to distribute all the channels across all the available resources as uniformly as possible, we use consistent hashing, with the underlying cluster discovery service providing consensus on both node health and hashring membership.

Achieving consensus via consistent placement algorithm in a hash ring

The placement mechanism is required not only to determine the initial placement of a role, but also to relocate the role whenever there is an event, such as node failure, that causes the role to move. Therefore, this dynamic placement mechanism is a core functionality in support of service continuity and reliability.

Detect, hash, resume

The first step in mitigating failure is detecting it. As discussed above, this is classically difficult because of the need to achieve near-simultaneous consensus between distributed entities. Once detected, the updated hashring state implies the new location of that resource, and from that point onward the channel and the state of the failed resource must resume in the new location with continuity.

Even though the role failed and there was resulting loss of state, there needs to be sufficient state persisted (and with sufficient redundancy) that resumption of the role is possible with continuity. Resumption with continuity is what enables the service to be reliable in the presence of this kind of failure; the state of each in-flight message is preserved across the role relocation. If we were unable to do that, and simply re-established the role without continuity of state, we could ensure service availability — but not reliability.

Channel persistence layer

When a message is published, we perform some processing, decide on success or failure, then respond to the call. The reliability guarantee means having certainty that once a message is acknowledged, all onward transmission implied by that will in fact take place. This in turn means that we can only acknowledge a message once we know for a fact that it is durably persisted, with sufficient redundancy that it cannot subsequently be lost.

First, we record the receipt of the message in at least two different availability zones (AZs). Then we have the same multiple-AZ redundancy requirement for the onward processing itself. This is the core of the persistence layer at Ably: we write a message to multiple locations, and we also make sure the process of writing it is transactional. You come away knowing the writing of the message was either not successful or unequivocally successful. With assurance of that, subsequent processing can be guaranteed to occur eventually, even if there are failures in the roles responsible for that processing.

Ensuring that messages are persisted in multiple AZs enables us to assume that failures in those zones are independent, so a single event or cause cannot lead to loss of data. Arranging for this placement requires AZ-aware orchestration, and ensuring that writes to multiple locations are actually transactional requires distributed consensus in the message persistence layer.

Structuring things this way allows us to start to quantify, probabilistically, the level of assurance. A service failure can only arise if there is a compound failure — that is, a failure in one AZ and, before that failure has been remediated, a failure in a second AZ.

In our mathematical model, when one node fails, we know how long it takes to detect and achieve consensus on the failure, and how long it takes subsequently to relocate the role. Knowing this, together with the failure rate of each AZ, it is possible to model the probability of an occurrence of a compound failure that results in loss of continuity of state. This is the basis on which we are able to provide our guarantee of eight 9s of reliability.

Implementation considerations

Even once you have a theoretical approach to achieving a particular aspect of fault tolerance, there are numerous practical and systems engineering aspects to consider in the wider context of the system as a whole. We give some examples below. To explore this topic further, read and/or watch our deep-dive on the topic, Hidden scaling issues of distributed systems — system design in the real world.

Consensus formation in globally-distributed systems

The mechanisms described above — such as the role placement algorithm — can only be effective when all of the participating entities are in agreement on the topology of the cluster together with the status and health of each node.

This is a classical consensus formation problem, where the members of a cluster, who might themselves be subject to failure, must agree on the status of one of their members. Consensus formation protocols such as Raft/Paxos are widely understood and have strong theoretical guarantees, but also have practical limitations in terms of scalability and bandwidth. In particular, they are not effective in networks spanning multiple regions because their efficiency breaks down if the latency becomes too high when communicating among peers.

Instead, our peers use the Gossip protocol, which is eventually-consistent, fault-tolerant, and can work across regions. Gossip is used among regions to share topology information as well as to construct a network map, and this broad cluster state consensus is then used as the basis for sharing various details cluster-wide.

Health is not binary

The classical theory that led to the development of Paxos and Raft originated from the recognition that failed or unhealthy entities oftentimes do not simply crash or stop responding. Instead, failing elements can exhibit partly-working behavior such as delayed responses, higher error rates or, in principle, arbitrary confusing or misleading behavior (see Byzantine fault). This issue is pervasive and even extends to the way a client interacts with the service.

When a client attempts connection to an endpoint in a given region, it is possible that the region is not available. If it’s entirely unavailable, then that’s a simple failure, and we would be able to detect that and redirect the client to greener pastures within the infrastructure. But what happens in practice is that regions can often be in a partially degraded state where they’re working some of the time. This means that the client itself has the problem of handling the failure — knowing where to redirect to obtain service, and knowing when to retry getting service from the default endpoint.

This is another example of the general fault tolerance problem: with many moving pieces, every single thing introduces additional complexity. If this part breaks, or that thing changes, how do you establish consensus on the existence of the change, the nature of the change, and the consequent plan of action?

Resource availability issues

At a very simple level, it is possible to provide redundant capacity only if the resources required are available. Occasionally there are situations where resources are simply unavailable at the moment they are demanded in a region, and it is necessary to offload demand to another region.

However, the resource availability problem also surfaces in a more challenging way when you realize that fault tolerance mechanisms themselves require resources to operate.

For example, there is a mechanism to manage the relocation of roles when the topology changes. This functionality itself requires resources in order to operate, such as CPU and memory on the affected instances.

But what if your disruption has come about precisely because your CPU or memory ran out? Now you’re attempting to handle those failures, but to do so you need… CPU and memory. This means that there are multiple dimensions in which you need to ensure that there exists a resource capacity margin, so that fault tolerance measures can be enacted at the time they are needed.

Resource scalability issues

Further to the point above, it’s not just about availability of resources, but also about the rate at which demand for them scales. In the steady, healthy state you might have N channels, N connections, and N messages with N capacity to deal with it all. Now imagine there is some failure and ensuing disruption for that cluster of N instances. If the amount of work required to compensate for the disruption is of size N², then maintaining the capacity margin becomes unsustainable, and the only available remediation is to fail over to an undisrupted region or cluster.

Simplistic fault tolerance mechanisms can exhibit this kind of O(N²) behavior or worse, so approaches need to be analyzed with this in mind. It’s another reminder that while things can fail just because they’re broken in some way, it’s also possible that they can go wrong because they have an unforeseen scale or complexity or some other unsustainable resource implication.

Conclusion

Fault tolerance is an approach to building systems able to withstand and mitigate adverse events and operating conditions in order to dependably continue delivering the level of service expected by the users of the system.

Dependability engineering in the physical world classically makes the distinction between availability and reliability and there are well-understood formulas for how to achieve each of these through fault tolerance and redundancy. At Ably we make the analogous distinction in the systems world between components that are stateless and those that are stateful.

Fault tolerance for stateless components is achieved in the same way as for availability in the physical world: through provision of redundant elements whose failure is statistically independent. Fault tolerance for stateful components can be compared to the physical reliability problem: it is the assurance of service without interruption. Continuity of state is essential in order that failures can be tolerated whilst preserving correctness and continuity of the provided service.

To be fault tolerant, a system must treat failures not as exceptional events, but as something expectedly routine. Unlike theoretical models of success and failure, threats to a system’s health in the real world are not binary and require complex theoretical and practical approaches to mitigate.

The Ably service is engineered with multiple layers that each make use of a wide range of fault tolerance mechanisms. In particular, we have confronted the hard engineering problems that arise which include stateful role placement, detection, hashing, and graceful resumption of service, among others. We’ve also articulated, and provide assurance of, the service guarantee at the channel persistence layer, such as assured onward processing once we acknowledge that we’ve received a message.

Beyond theoretical approaches, designing fault tolerant systems involves numerous real-world systems engineering challenges. This includes infrastructure availability and scalability issues, as well as dealing with consensus formation and orchestration of ever-fluctuating topologies of all clusters and nodes in the globally-distributed system, with unpredictable/hard-to-detect health status of any given entity on the network.

The Ably platform was designed from the ground up with these principles in mind, with the goal of delivering the best-in-class enterprise solution. This is why we can confidently provide our service-level guarantees of both availability and reliability – and thus dependability and fault tolerance.

Get in touch to learn more about Ably and how we can help you deliver seamless realtime experiences to your customers.