Fighting the Ecosystem Wars in the Proactive Cloud

This article is a chapter from my book Explain the Cloud Like I'm 10. It has 30 reviews on Amazon! If you like this chapter then you'll love the book.

The cloud is always busy proactively working for you in the background. That’s how cloud services compete with each other to keep you in their ecosystem.

Most of the cloud services we’ve talked about so far have been request driven. You initiate a request and the cloud does something for you. You read a book. You search for the nearest coffee shop. You navigate to a destination. You send a message. You play a movie.

Handling direct requests is not all a cloud is good for. In fact, the biggest potential of the cloud is how it can proactively perform jobs for you in the background, without you asking or even knowing that it can be done.

Let’s set this up:

- The cloud has a lot of compute power.

- The cloud has all your data.

- The cloud has access to a lot of other data in the world.

- Cloud providers have a lot of very smart programmers.

- As a cloud customer, you represent a very valuable recurring revenue stream.

- To keep your business and keep you within their ecosystem, cloud companies want to continually surprise and delight you.

How does a cloud company surprise and delight you?

- By adding new features. The more features you use, the more likely you’ll stay in their ecosystem of services.

- By inventing really clever products that can only be done with a lot of compute power, a lot of data, and a lot of smart programmers.

Competition is driving the cloud to become proactive. Proactive means taking action to control a situation rather than just responding to it after it has happened.

What kind of actions? Those are the clever features and inventions, we’ll talk more about these in a moment.

The key point to understand is: the list of jobs cloud services will perform for you will only grow. And grow. And grow. And grow.

Why? We are in the middle of the ecosystem wars. Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and anyone else brave enough to play in the cloud space, want you to keep using their services and only their services.

The more valuable features they add, the greater the gravitational attraction to their service.

What do I mean by ecosystem?

An ecosystem—from a software perspective—is a community of interacting services in a single provider’s environment.

I’ll illustrate using a personal example. When Amazon released their Echo product, I bought it immediately.

If you don’t already know, Amazon Echo is a hands-free speaker you control with your voice. Echo connects to the Alexa Voice Service to play music, make calls, send and receive messages, provide information, news, sports scores, weather, and more—instantly. All you have to do is ask.

It’s like Apple’s Siri; only you don’t need your phone to use it. Our Echo sits on our kitchen counter.

We mostly use Echo to play music, listen to radio stations, set timers when cooking, ask about the weather, and occasionally ask general questions.

To talk to an Echo, you lead with the keyword Alexa and then speak a command. It’s just how you would talk to Siri.

Here are some example Alexa commands:

- Alexa, set timer for 5 minutes

- Alexa, increase volume

- Alexa, give me my Flash Briefing

- Alexa, what's on my calendar for today?

- Alexa, turn on the lights

- Alexa, order walnuts

There are thousands more. Let’s go through an example in more detail. The example should feel familiar because Alexa is a cloud service and works like all the cloud services we’ve talked about. The difference is instead of using an app or a web page, you talk to a device that sits on a nearby table.

Let’s say I’m standing in my kitchen and say, “Alexa, play Etta James.”

The Echo is listening all the time for the keyword Alexa. As soon as the Echo hears me say Alexa, it starts paying attention and recording what I say until I stop talking.

When the Echo thinks I have stopped talking, it sends the complete sentence to Amazon’s cloud. The Echo device itself isn’t capable of doing very much at all. The smarts are in the cloud.

The Amazon cloud receives my command.

Inside Amazon’s cloud, possibly hundreds of computers are put to work figuring out what I said and what I want to have happen. Computers understand what humans say using natural language processing software.

The software parses what I said, and hears play, so it knows I want to play something. But what?

Amazon extracts Etta James after play in the sentence. Amazon now knows I want to play Etta James. How does Amazon figure out what I mean by Etta James?

A few years ago we uploaded all our old CDs into Amazon’s music service. In it, we have a lot of music by Etta; she was an awesome singer.

What Amazon does is search our music library for a match. It looks to see if I have any music by Etta James. And sure enough, it finds that we do. Amazon immediately starts randomly playing a selection of her songs through our Echo.

Result! That’s exactly what I wanted to have happen. But what if I didn’t have any music by Etta James? Amazon would have kept searching different sources for a match. It would try Pandora, a list of radio stations, it’s own music service, and probably a hundred other sources I have no idea about.

Because Amazon could have hundreds of computers working on this one problem in parallel, it can do all this work really fast. Amazon literally searches every possible source of potential Etta James matches at the same time. All the answers are combined and the best answer is selected from the options. That’s the power of the cloud. A search on your device could never be as fast or look in as many different places for a match.

Notice we have a little ecosystem going on here. Echo is one part of the ecosystem. Our uploaded music is another part of the ecosystem. Over time we have configured Pandora with our preferences. That’s part of the ecosystem. All the music we’ve ever purchased from Amazon is also part of the ecosystem. We have purchased Kindle books with audio narration. That’s part of the ecosystem.

We haven’t, but other people have configured their Echo to turn lights on and off, to open doors, to change the temperature, and hundreds of other smart home related tricks. That’s part of their ecosystem.

We don’t, but you can directly call another Echo owner and talk to them over your Echo. It’s like a phone call using an Echo device as a phone. If you have an elderly parent and the Echo is how they can call you in an emergency, without having to dial a number, that’s a very important part of an ecosystem.

You can start to see how an ecosystem is made up of a system services that build on each other and work together to provide you valuable services. Once we find value in something, we are reluctant to give it up, and that’s why we have the ecosystem wars.

What do I mean by ecosystem wars?

Every cloud service you use from a cloud provider increases switching costs. Say, for example, you are tired of your Echo and would like to switch to Google Home.

This is exactly my situation right now. The problem with Alexa is that she’s as dumb as a post. I mean no disrespect. Alexa does a lot of things well, but ask her any kind of difficult question, and the chances are she’ll have no idea what you’re talking about. It’s maddening. Also, Alexa does not learn. Every morning I ask her to play the same radio station and she gets it wrong as often as not.

Google is the leader in AI, so I think Google Home would do a much better job at answering my questions. The problem is we have tied ourselves to Amazon’s ecosystem.

Do I really want to switch bad enough that I’ll move all my music to Google? Do I really want to go through the process of Google learning all my preferences? Do I want to forgo having Kindle ebooks read over the Echo?

I honestly don’t know. And that’s what sucks about ecosystems. From a customer perspective, we want to have it all. We want to pick and choose and have everything just work.

That’s not reality, unfortunately. Every major platform wants to create features that are so enticing you’ll adopt their ecosystem and never considering moving to another.

That sort of loyalty is worth lots of money, and that’s why there’s an ecosystem war for your business. Amazon has the early lead, a significant lead, but competition is heating up.

Or I could switch to the Apple ecosystem. I already have an iPhone. I could pay for Apple Music and stream music instead of worrying about preserving old albums. I could take it one step further and get the new LTE watch and stream music over the watch to my new Apple EarPods. That sounds cool. And Apple has their HomePod that I can use to replace my Echo. But I don’t think so. Siri is even dumber than Alexa, so that wouldn’t be a win.

You can tell competition is fierce by how the ecosystems treat each other. You can buy everything on Amazon, right? Search for Google Home on Amazon. You won’t find it. Amazon doesn’t allow Google Home to be sold on Amazon.

Until recently the Amazon Prime Video app was not available on Apple TV. It took negotiation between Apple and Amazon to make it happen. Amazon doesn’t sell Google’s Chromecast and other Google gear, nor does Amazon sell Apple TV devices.

See how this works? These are the kind of decisions Apple, Google, and Amazon want us to make. They want to force us into adopting one ecosystem: theirs. We don’t get to have it all.

Petty? Childish? Bad for customers? Yes, I think so. But that’s how seriously all the players take this ecosystem stuff.

It’s war. A war for customers.

In a way picking a service is a lot like getting married. When you get married, you’re marrying into a new family. When picking a service, you’re marrying into an ecosystem. Pick your in-laws well.

Facebook Memories

Facebook loves to do little things for us in the background. The goal is to keep us spending more time on Facebook. And it works.

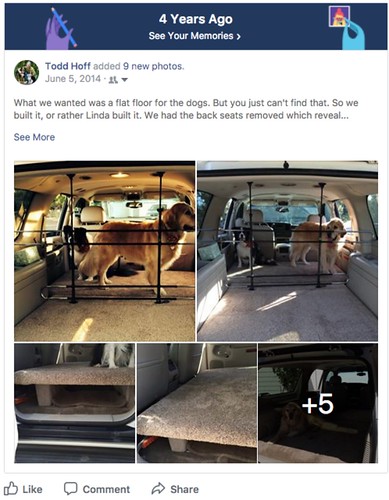

Here’s an example of Facebook surfacing a memory of mine from 3 years ago. It’s our car just before we were about to set off on a cross-country trip.

Birthdays are another example of Facebook doing stuff for us in the background. Facebook reminds us of everyone’s birthdays and even creates a personal video to share for the occasion.

What does ‘in the background’ mean?

When something happens in the background, it happens behind the scenes. You don’t ask for it. Like sausage, you don’t see it being made, you don’t care how it gets made, but it magically shows up in the grocery store every day.

That’s how Facebook Memories works, in the background.

Facebook creates Memories for all two billion of its users. Can you imagine all the computers working their CPUs to the bone to do all this for us?

Did anyone ask for Memories? No. Facebook thought we’d like this feature, so they used all their data, cloud computing capacity, and programming talent to make it happen.

Memories is implemented in Facebook’s cloud. It runs in Facebook’s cloud continuously. Facebook is always generating Memories without anyone making a request. So, its happens proactively in the background.

We’ll see more and more proactive features as time goes on. Once you have data in the cloud, there’s no end of clever features that can made.

Google Photos

Google Photos is Google’s service for storing and organizing photos

All the photos I take on my iPhone upload to Google Photos. Why not use Apple’s photo app? Because Google Photos is so much better, largely because it’s a cloud service. Google processes all uploaded photos in their cloud.

Apple only processes photos locally on each device. Apple has better privacy, but Google has better AI, and it lets you do some incredible things.

Ask Google Photos to see all your pictures of dogs and it will find every picture you have with a dog in it.

Here are the first few pictures of what Google Photos returns when I ask to see all my dog pictures. I have a lot of dog pictures.

How does a computer know what a dog looks like? Through AI (artificial intelligence). Google has trained software to look at a photo and know when it contains an image of a dog.

That’s just the start of what you can do. You can ask to see all pictures containing the color blue, or pictures with clouds, or pictures taken in California, or pictures taken at a certain time or date range, or pictures of an event.

It’s amazing. The AI Google uses to search photos is incredibly powerful.

One huge benefit is you don’t have to spend hours painstakingly organizing photos anymore (which admit it, you never did anyway). Just search for what you want, and Google will organize the results for you.

That’s the power of the cloud, and it will only get better over time as Google’s AI improves.

So that’s Google Photos the cloud service, what does Photos do for us proactively?

Google Photos likes to use AI to “improve” your pictures.

Here’s an example of what Google calls Stylized photos. My original photo looks like:

One day Google notified me it thought my picture could look better. Here’s what it came up with:

Google applied some tweaks to my picture. Does Google’s photo better look than mine? I don’t think so in this case, but some changes it makes look pretty cool.

The point of the story is that improving photos is something Google does proactively. Somewhere in Google’s cloud an AI looks at all your pictures, determines which ones it thinks it can improve, makes those improvements, and proudly shows you its handiwork.

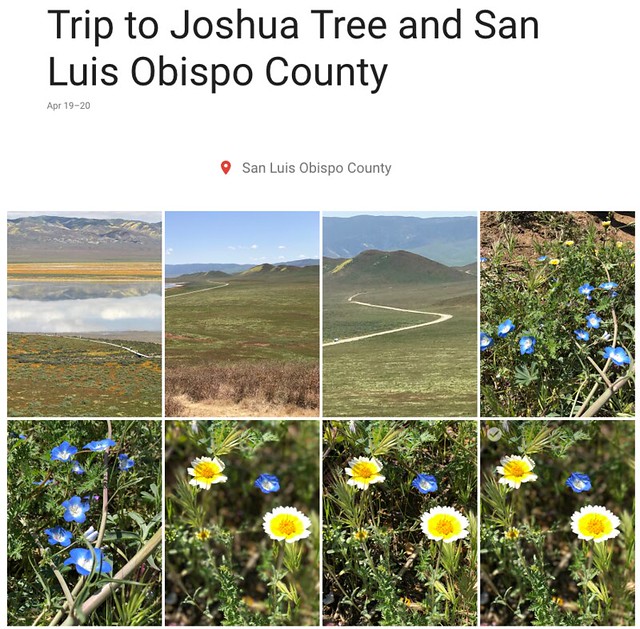

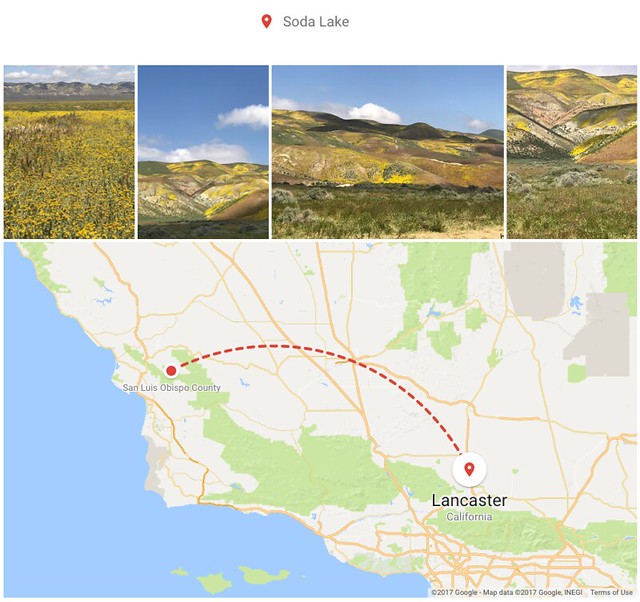

While Stylized photos are cool, much cooler are the trip Albums Google automatically puts together.

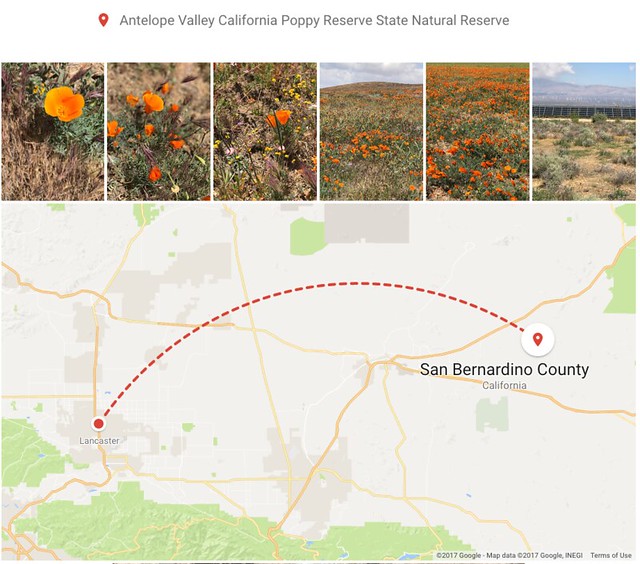

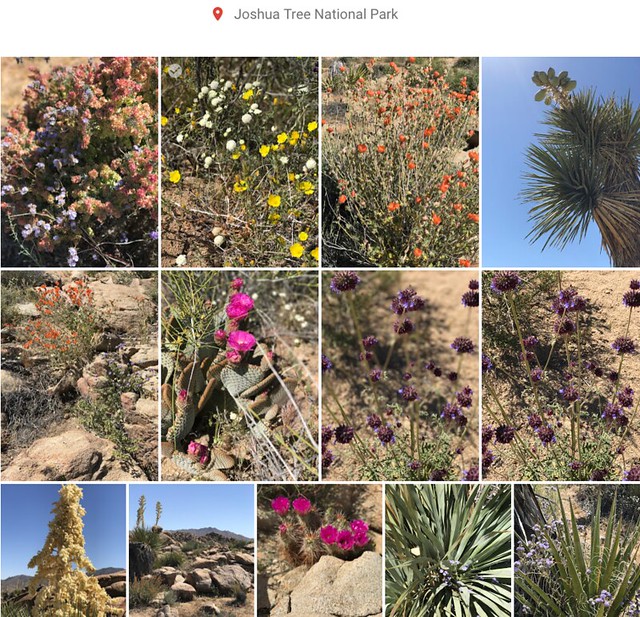

The extraordinary rains we received in California in 2016 made for an incredible wildflower season. We decided to go on a road trip and take a look. As you might imagine, I took a lot of photos.

Here’s an example of an album Google put together of our wildflower trip:

I did not make this. Google put this album together, automatically, on its own, and shared it with me.

Somewhere in Google’s cloud software noticed my photos were close together in time and space, so it figured I must have taken a trip. It probably looks at the pictures and thinks to itself, “yeah, those look pretty good, let’s make an album. Todd will really like that.”

And Google was right. I loved the album. Mostly I loved not having to make it myself! Albums are so much work to create. I have lots of albums like this that Google has made for me of various trips.

Google makes other things as well. If Google notices photos were taken close together, it will combine them into an animation. I’d show you, but you can’t see animations in a book.

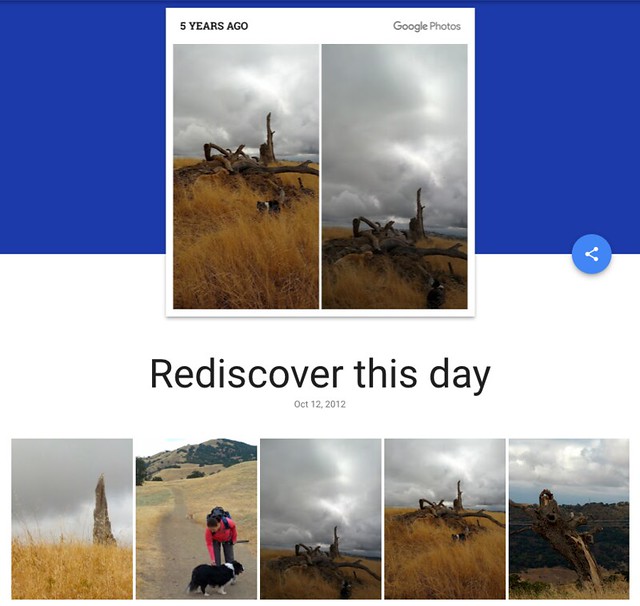

Google also has it’s own feature, similar to Facebook Memories, that it calls Rediscover This Day.

The larger point is Google has built an AI that understands video and photos at a deep level. Google uses that knowledge and the power of its cloud to make delightful creations in the background.

This has never been done before because it never could be done before. I can’t wait to see what they create next.

Google Home

Google Home is Google’s version of the Amazon Echo. I showed a picture of it earlier in this chapter.

Like Amazon Echo, Google Home can do a lot of cool stuff:

- OK Google, order an Uber.

- Hey Google, remind me to buy strawberries next time I’m at the Costco in Santa Cruz

- OK Google, reorder Old Spice deodorant.

- Hey Google, How long is my commute?

- Hey Google, make it cooler.

- Hey Google, where is Alaska Flight 21 right now?

- OK Google, call mom.

- Hey Google, add pick Linda up at 6:00 today to my calendar

- OK Google, remember that the house keys are in the bushes

The Echo is still the winner in the shear number of different things it can do. Google’s playing from behind, but it’s catching up.

What Google hopes is its lead in AI technology will attract users to their ecosystem. How? By Google Home being able to do smarter and more sophisticated things than anyone else.

Here’s an example of something Google can do that Amazon can’t do: “Hey Google, remind me to buy strawberries next time I’m at the Costco in Santa Cruz.”

Let’s unpack this. Google Home is a cloud service, so it works like the Echo. Google Home notices I said Hey Google. It then passes whatever I say to Google’s cloud. Like the Echo, possibly hundreds of computers will work on figuring out what I said, what I meant, and what I want to have happen.

Google will see that I said remind me. So it knows I’m creating a reminder. A reminder for what? A reminder to buy strawberries. The difference here is Google knows what strawberries are. It knows strawberries can be bought in stores and it uses that information to create richer services.

That’s why Google can make sense of next time I’m at the Costco in Santa Cruz. Like a human Google can reason from my wanting a thing called a strawberry, to knowing what next time means, and knowing what Costco in Santa Cruz means, to build an alert that will notify me once and only once that I should buy strawberries if I’m in the store.

To make this work, Google has to have a lot of practical knowledge. It has to understand what next time means. It has to understand Costco in Santa Cruz is a particular physical location. I can’t be at just any store, or any Costco, or anywhere in Santa Cruz. I must be in the Costco in Santa Cruz. Nowhere else.

That’s powerful stuff. It’s not simple at all to implement. In Google’s cloud, there’s some piece of software that’s constantly watching my location and then triggering the notification. When I leave the store it must know to cancel the alert because that’s what next time means. It gets complicated fast.

And Google is doing this for potentially billions of people, all over the world, all of which may have multiple such reminders outstanding at anyone time.

Now that’s proactive and in the background.

Sophisticated proactive services like these will become the norm as AI gets better, as clouds become more powerful, and ecosystems try even harder to capture you into their orbit.