The Quest for Database Scale: the 1 M TPS challenge - Three Design Points and Five common Bottlenecks to avoid

This a guest post by Rajkumar Iyer, a Member of Technical Staff at Aerospike.

About a year ago, Aerospike embarked upon a quest to increase in-memory database performance - 1 Million TPS on a single inexpensive commodity server. NoSQL has the reputation of speed, and we saw great benefit from improving latency and throughput of cacheless architectures. At that time, we took a version of Aerospike delivering about 200K TPS, improved a few things - performance went to 500k TPS - and published the Aerospike 2.0 Community Edition. We then used kernel tuning techniques and published the recipe for how we achieved 1 M TPS on $5k of hardware.

This year we continued the quest. Our goal was to achieve 1 Million database transactions per second per server; more than doubling previous performance. This compares to Cassandra’s boast of 1M TPS on over 300 servers in Google Compute Engine - at a cost of $2 million dollars per year. We achieved this without kernel tuning.

This article describes the three design points we kept in mind and the five common bottlenecks we avoided to create a simpler recipe you can follow for high performance operations with Aerospike.

Three Design Points

Any distributed database system that operates with such intensity must be architected with 3 design points in mind:

1) Stability - is achieved by simplicity and short, understandable code paths. Keeping each function slim and trim goes a long way to making sure the full system operates smoothly even when multiple such layers are stacked over one another. Any complex or esoteric logic makes the system very hard to maintain, and should be, at best, minimized and kept isolated.

2) Predictability - is provided by writing the database in C and using only a few external libraries. Predicting the actions of your code means having complete control over precisely what the system is doing and painstakingly making sure that all resources are utilized efficiently. Aerospike doesn’t use ‘libeio’ or ‘libev’ or any other library for networking. It also doesn’t use memory mapping -- instead it calls read and write operations itself. So even though languages such as Java and Erlang may have reduced the overall development time, choosing C was optimal.

3) Scalability - by scaling both up and out. Vertical scaling along the lines of old school RDBMSs works in only some use cases, but neither does a dumb approach with massive scale out clusters where resources go underutilized. Costs escalate and management is a challenge at best - a distributed system can never be correct or predictable as it grows and failure rates increase. A balanced approach is best. Right from the start we designed Aerospike to scale both up and out, maximizing server utilization with transaction speeds per server 10x better than other NoSQL options, and yet also allowing in-service addition and removal of servers.

In addition, databases don’t exist in isolation, they must be architected as part of the full stack, so that the end to end system scales. A scale out database must take care of all clustering functions, not push the load to the app, for example, for sharding or load balancing. Any database that shifts its complexity to the app cannot be part of a truly high scale operation.

Five Common Bottlenecks

To successfully scale up to over 1 M TPS on a single server, any database system has to effectively avoid 5 common bottlenecks:

1) Network Overhead

For any over the wire client-server architecture, the #1 bottleneck is the cost of moving a packet across the network and from the network card to the kernel and on to the user space. Our previous effort required special binding of irq to multiple queues in the NIC to balance load. Since then, the stock irqbalance has become much smarter, reducing the work we have to do.

Options like the Intel Data Plane Development Kit (DPDK) completely eliminate TCP stack overhead and let user space functions deal with network packets. However, DPDK does not handle TCP/IP, nor does it handle large requests, so the database system has to do it’s own flow control. Unless DPDK is supported and more widely accepted, optimizing general purpose databases to use DPDK is still in the future.

2) NUMA Overhead

The second bottleneck is the cost of moving data across NUMA regions. In an ideal world, the database server should be a single threaded event loop with no context switching - but there are two major drawbacks with this approach. First, database systems must manage a lot of different tasks - long running jobs, short running jobs, disk I/O, network communication, and buffering requests to handle occasional peaks. Building such a system as a single event loop makes things massively complicated. Second, parallelizing such a system, going from single core to multi-core requires a lot of logic to be offloaded to the database client.

Allowing multi-threaded processes to run over multi-core multi-socket machines however has the problem of shared data moving across multiple NUMA regions. To avoid single core implementations and NUMA overhead, the balanced approach is to build a system that scales by grouping multiple threads per CPU socket instead of per core with a single threaded system. This makes sure no shared data is accessed across multiple NUMA regions and also allows the system to use simpler logical threads.

3) Context Switching Overhead

In a multi-threaded system, it is very easy to create a lot of threads, but unless this is done carefully, context switching is where the system bottlenecks. As much as possible, operations should be written single threaded rather than passing requests from one thread to another.

4) Memory Bus Delays

The next big bottleneck is around CPU stalls - when the CPU is not doing anything, waiting for data to be fetched, or because of branch mis-prediction. The way around this problem is to

- Carefully design data structures to make sure that frequently and commonly accessed data has locality and falls within a single cache line.

- Minimize the number of branch instructions. This is reverse predicate push, where all the branching is done upfront and the main logic contains the smallest number of branch instructions.

In production systems like Aerospike, it is not just the functional aspects but also system monitoring and debugging code which needs to be built-in and optimized. Such secondary data should always be local to a thread and should be consolidated at query time to avoid unnecessary data movement from one core to another.

5) Cross Cluster Chatter

Fundamental to scaling up and out, the system needs to be near 100% shared nothing - minimizing cross cluster synchronization chatter. In Aerospike, data is partitioned using a simple algorithm and access paths are structured at every level so that each thread can operate without contention. The first indication of very high contention is low CPU utilization - similar to that observed when MongoDB runs when processing write loads on multi-core machines.

Results

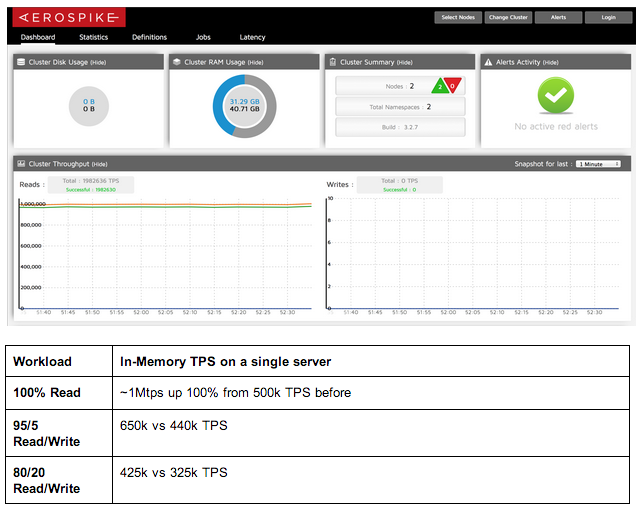

The new (4 step recipe) was then used to run the same tests with 2 nodes, 50 million records, each record with 128 bytes of data replicated by a factor of 2. Compared to the previous results, this new recipe saw substantial performance improvements by using Aerospike Community Edition 3.2.8 on Centos 6.3:

Related Articles

- The new 4 step recipe, detailed specifications and instructions for running these tests are published here.

- Russ’ 10 Ingredient Recipe For Making 1 Million TPS On $5K Hardware

- Wide Fast SATA: The Recipe For Hot Performance

- 42 Monster Problems That Attack As Loads Increase