The Architecture Twitter Uses to Deal with 150M Active Users, 300K QPS, a 22 MB/S Firehose, and Send Tweets in Under 5 Seconds

Toy solutions solving Twitter’s “problems” are a favorite scalability trope. Everybody has this idea that Twitter is easy. With a little architectural hand waving we have a scalable Twitter, just that simple. Well, it’s not that simple as Raffi Krikorian, VP of Engineering at Twitter, describes in his superb and very detailed presentation on Timelines at Scale. If you want to know how Twitter works - then start here.

It happened gradually so you may have missed it, but Twitter has grown up. It started as a struggling three-tierish Ruby on Rails website to become a beautifully service driven core that we actually go to now to see if other services are down. Quite a change.

Twitter now has 150M world wide active users, handles 300K QPS to generate timelines, and a firehose that churns out 22 MB/sec. 400 million tweets a day flow through the system and it can take up to 5 minutes for a tweet to flow from Lady Gaga’s fingers to her 31 million followers.

A couple of points stood out:

- Twitter no longer wants to be a web app. Twitter wants to be a set of APIs that power mobile clients worldwide, acting as one of the largest real-time event busses on the planet.

- Twitter is primarily a consumption mechanism, not a production mechanism. 300K QPS are spent reading timelines and only 6000 requests per second are spent on writes.

- Outliers, those with huge follower lists, are becoming a common case. Sending a tweet from a user with a lot of followers, that is with a large fanout, can be slow. Twitter tries to do it under 5 seconds, but it doesn’t always work, especially when celebrities tweet and tweet each other, which is happening more and more. One of the consequences is replies can arrive before the original tweet is received. Twitter is changing from doing all the work on writes to doing more work on reads for high value users.

- Your home timeline sits in a Redis cluster and has a maximum of 800 entries.

- Twitter knows a lot about you from who you follow and what links you click on. Much can be implied by the implicit social contract when bidirectional follows don’t exist.

- Users care about tweets, but the text of the tweet is almost irrelevant to most of Twitter's infrastructure.

- It takes a very sophisticated monitoring and debugging system to trace down performance problems in a complicated stack. And the ghost of legacy decisions past always haunt the system.

How does Twitter work? Read this gloss of Raffi’s excellent talk and find out...

The Challenge

- At 150 million users with 300K QPS for timelines (home and search) naive materialization can be slow.

- Naive materialization is a massive select statement over all of Twitter. It was tried and died.

- Solution is a write based fanout approach. Do a lot of processing when tweets arrive to figure out where tweets should go. This makes read time access fast and easy. Don’t do any computation on reads. With all the work being performed on the write path ingest rates are slower than the read path, on the order of 4000 QPS.

Groups

- The Platform Services group is responsible for the core scalable infrastructure of Twitter.

- They run things called the Timeline Service, Tweet Service, User Service, Social Graph Service, all the machinery that powers the Twitter platform.

- Internal clients use roughly the same API as external clients.

- 1+ millions apps are registered against 3rd party APIs

- Contract with product teams is that they don’t have to worry about scale.

- Work on capacity planning, architecting scalable backend systems, constantly replacing infrastructure as the site grows in unexpected ways.

- Twitter has an architecture group. Concerned with overall holistic architecture of Twitter. Maintains technical debt list (what they want to get rid of).

Push Me Pull Me

- People are creating content on Twitter all the time. The job of Twitter is to figure out how to syndicate the content out. How to send it to your followers.

- The real challenge is the real-time constraint. Goal is to have a message flow to a user in no more than 5 seconds.

- Delivery means gathering content and exerting pressure on the Internet to get it back out again as fast as possible.

- Delivery is to in-memory timeline clusters, push notifications, emails that are triggered, all the iOS notifications as well as Blackberry and Android, SMSs.

- Twitter is the largest generator of SMSs on a per active user basis of anyone in the world.

- Elections can be one of the biggest drivers of content coming in and fanouts of content going out.

- Two main types of timelines: user timeline and home timeline.

- A user timeline is all the tweets a particular user has sent.

- A home timeline is a temporal merge of all the user timelines of the people are you are following.

- Business rules are applied. @replies of people that you don’t follow are stripped out. Retweets from a user can be filtered out.

- Doing this at the scale of Twitter is challenging.

- Pull based

- Targeted timeline. Things like twitter.com and home_timeline API. Tweets delivered to you because you asked to see them. Pull based delivery: you are requesting this data from Twitter via a REST API call.

- Query timeline. Search API. A query against the corpus. Return all the tweets that match a particular query as fast as you can.

- Push based

- Twitter runs one of the largest real-time event systems pushing tweets at 22 MB/sec through the Firehose.

- Open a socket to Twitter and they will push all public tweets to you within 150 msec.

- At any given time there’s about 1 million sockets open to the push cluster.

- Goes to firehose clients like search engines. All public tweets go out these sockets.

- No, you can’t have it. (You can’t handle/afford the truth.)

- User stream connection. Powers TweetDeck and Twitter for Mac also goes through here. When you login they look at your social graph and only send messages out from people you follow, recreating the home timeline experience. Instead of polling you get the same timeline experience over a persistent connection.

- Query API. Issue a standing query against tweets. As tweets are created and found matching the the query they are routed out the registered sockets for the query.

- Twitter runs one of the largest real-time event systems pushing tweets at 22 MB/sec through the Firehose.

High Level for Pull Based Timelines

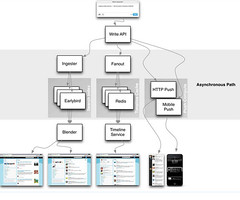

- Tweet comes in over a write API. It goes through load balancers and a TFE (Twitter Front End) and other stuff that won’t be addressed.

- This is a very directed path. Completely precomputed home timeline. All the business rules get executed as tweets come in.

- Immediately the fanout process occurs. Tweets that come in are placed into a massive Redis cluster. Each tweet is replicated 3 times on 3 different machines. At Twitter scale many machines fail a day.

- Fanout queries the social graph service that is based on Flock. Flock maintains the follower and followings lists.

- Flock returns the social graph for a recipient and starts iterating through all the timelines stored in the Redis cluster.

- The Redis cluster has a couple of terabytes of RAM.

- Pipelined 4k destinations at a time

- Native list structure are used inside Redis.

- Let’s say you tweet and you have 20K followers. What the fanout daemon will do is look up the location of all 20K users inside the Redis cluster. Then it will start inserting the Tweet ID of the tweet into all those lists throughout the Redis cluster. So for every write of a tweet as many as 20K inserts are occurring across the Redis cluster.

- What is being stored is the tweet ID of the generated tweet, the user ID of the originator of the tweet, and 4 bytes of bits used to mark if it’s a retweet or a reply or something else.

- Your home timeline sits in a Redis cluster and is 800 entries long. If you page back long enough you’ll hit the limit. RAM is the limiting resource determining how long your current tweet set can be.

- Every active user is stored in RAM to keep latencies down.

- Active user is someone who has logged into Twitter within 30 days, which can change depending on cache capacity or Twitter’s usage.

- If you are not an active user then the tweet does not go into the cache.

- Only your home timelines hit disk.

- If you fall out of the Redis cluster then you go through a process called reconstruction.

- Query against the social graph service. Figure out who you follow. Hit disk for every single one of them and then shove them back into Redis.

- It’s MySQL handling disk storage via Gizzard, which abstracts away SQL transactions and provides global replication.

- By replicating 3 times if a machine has a problem then they won’t have to recreate the timelines for all the timelines on that machine per datacenter.

- If a tweet is actually a retweet then a pointer is stored to the original tweet.

- When you query for your home timeline the Timeline Service is queried. The Timeline Service then only has to find one machine that has your home timeline on it.

- Effectively running 3 different hash rings because your timeline is in 3 different places.

- They find the first one they can get to fastest and return it as fast as they can.

- The tradeoff is fanout takes a little longer, but the read process is fast. About 2 seconds from a cold cache to the browser. For an API call it’s about 400 msec.

- Since the timeline only contains tweet IDs they must “hydrate” those tweets, that is find the text of the tweets. Given an array of IDs they can do a multiget and get the tweets in parallel from T-bird.

- Gizmoduck is the user service and Tweetypie is the tweet object service. Each service has their own caches. The user cache is a memcache cluster that has the entire user base in cache. Tweetypie has about the last month and half of tweets stored in its memcache cluster. These are exposed to internal customers.

- Some read time filtering happens at the edge. For example, filtering out Nazi content in France, so there’s read time stripping of the content before it is sent out.

High Level for Search

- Opposite of pull. All computed on the read path which makes the write path simple.

- As a tweet comes in, the Ingester tokenizes and figures out everything they want to index against and stuffs it into a single Early Bird machine. Early Bird is a modified version of Lucene. The index is stored in RAM.

- In fanout a tweet may be stored in N home timelines of how many people are following you, in Early Bird a tweet is only stored in one Early Bird machine (except for replication).

- Blender creates the search timeline. It has to scatter-gather across the datacenter. It queries every Early Bird shard and asks do you have content that matches this query? If you ask for “New York Times” all shards are queried, the results are returned, sorted, merged, and reranked. Rerank is by social proof, which means looking at the number of retweets, favorites, and replies.

- The activity information is computed on a write basis, there’s an activity timeline. As you are favoriting and replying to tweets an activity timeline is maintained, similar to the home timeline, it is a series of IDs of pieces of activity, so there’s favorite ID, a reply ID, etc.

- All this is fed into the Blender. On the read path it recomputes, merges, and sorts. Returning what you see as the search timeline.

- Discovery is a customized search based on what they know about you. And they know a lot because you follow a lot of people, click on links, that information is used in the discovery search. It reranks based on the information it has gleaned about you.

Search and Pull are Inverses

- Search and pull look remarkably similar but they have a property that is inverted from each other.

- On the home timeline:

- Write. when a tweet comes in there’s an O(n) process to write to Redis clusters, where n is the number of people following you. Painful for Lady Gaga and Barack Obama where they are doing 10s of millions of inserts across the cluster. All the Redis clusters are backing disk, the Flock cluster stores the user timeline to disk, but usually timelines are found in RAM in the Redis cluster.

- Read. Via API or the web it’s 0(1) to find the right Redis machine. Twitter is optimized to be highly available on the read path on the home timeline. Read path is in the 10s of milliseconds. Twitter is primarily a consumption mechanism, not a production mechanism. 300K requests per second for reading and 6000 RPS for writing.

- On the search timeline:

- Write. when a tweet comes in and hits the Ingester only one Early Bird machine is hit. Write time path is O(1). A single tweet is ingested in under 5 seconds between the queuing and processing to find the one Early Bird to write it to.

- Read. When a read comes in it must do an 0(n) read across the cluster. Most people don’t use search so they can be efficient on how to store tweets for search. But they pay for it in time. Reading is on the order of 100 msecs. Search never hits disk. The entire Lucene index is in RAM so scatter-gather reading is efficient as they never hit disk.

- Text of the tweet is almost irrelevant to most of the infrastructure. T-bird stores the entire corpus of tweets. Most of the text of a tweet is in RAM. If not then hit T-bird and do a select query to get them back out again. Text is almost irrelevant except perhaps on Search, Trends, or What’s Happening pipelines. The home timeline doesn’t care almost at all.

The Future

- How to make this pipeline faster and more efficient?

- Fanout can be slow. Try to do it under 5 seconds but doesn’t work sometimes. Very hard, especially when celebrities tweet, which is happening more and more.

- Twitter follow graph is an asymmetric follow. Tweets are only rendered onto people that are following at a given time. Twitter knows a lot about you because you may follow Lance Armstrong but he doesn’t follow you back. Much can be implied by the implicit social contract when bidirectional follows don’t exist.

- Problem is for large cardinality graphs. @ladygaga has 31 million followers. @katyperry has 28 million followers. @justinbieber has 28 million followers. @barackobama has 23 million followers.

- It’s a lot of tweets to write in the datacenter when one of these people tweets. It’s especially challenging when they start talking to each other, which happens all the time.

- These high fanout users are the biggest challenge for Twitter. Replies are being seen all the time before the original tweets for celebrities. They introduce race conditions throughout the site. If it takes minutes for a tweet from Lady Gaga to fanout then people are seeing her tweets at different points in time. Someone who followed Lady Gaga recently could see her tweets potentially 5 minutes before someone who followed her far in the past. Let’s say a person on the early receive list replies then the fanout for that reply is being processed while her fanout is still occurring so the reply is injected before the original tweet in the people receiving her tweets later. Causes much user confusion. Tweets are sorted by ID before going out because they are mostly monotonically increasing, but that doesn’t solve the problem at that scale. Queues back up all the time for high value fanouts.

- Trying to figure out how to merge the read and write paths. Not fanning out the high value users anymore. For people like Taylor Swift don’t bother with fanout anymore, instead merge in her timeline at read time. Balances read and write paths. Saves 10s of percents of computational resources.

Decoupling

- Tweets are forked off in many different ways, mostly to decouple teams from each other. The search, push, interest email, and home timeline teams can work independently of each other.

- For performance reasons the system has been being decoupled. Twitter used to be fully synchronous. That stopped 2 years ago for performance reasons. Ingesting a tweet into the tweet API takes up to 145 msecs and then all the clients are disconnected. This is for legacy reasons. The write path is powered by Ruby through the MRI, a single threaded server, processing power is being eaten up every time a Unicorn worker is allocated. They want to be able to release a client connection as fast as they can. A tweet comes in. Ruby ingests it. Sticks it into a queue and disconnects. They only run about 45-48 processes per box so they can only ingest that many tweets simultaneously per box so they want to disconnect as fast as they can.

- The tweets are handed off to the asynchronous pathway where all the stuff we’ve been talking about kicks in.

Monitoring

- Dashboards around the office show how the system is performing at any given time.

- If you have 1 million followers it takes a couple of seconds to fanout all the tweets.

- Tweet input statistics: 400m tweets per day; 5K/sec daily average; 7K/sec daily peak; >12K/sec during large events.

- Timeline delivery statistics: 30b deliveries / day (~21m / min); 3.5 seconds @ p50 (50th percentile) to deliver to 1m; 300k deliveries /sec; @ p99 it could take up to 5 minutes

- A system called VIZ monitors every cluster. Median request time to the Timeline Service to get data out of Scala cluster is 5msec. @ p99 it’s 100msec. And @ p99.9 is where they hit disk, so it takes a couple hundred of milliseconds.

- Zipkin is based on Google’s Dapper system. With it they can taint a request and see every single service it hits, with request times, so they can get a very detailed idea of performance for each request. You can then drill down and see every single request and understand all the different timings. A lot of time is spent debugging the system by looking at where time is being spent on requests. They can also present aggregate statistics by phase, to see how long fanout or delivery took, for example. It was a 2 year project to get the get for the activities user timeline down to 2 msec. A lot of time was spent fighting GC pauses, fighting memcache lookups, understanding what the topology of the datacenter looks like, and really setting up the clusters for this type of success.

Related Articles

- Why Are Facebook, Digg, And Twitter So Hard To Scale?

- On Reddit

- On Hacker News

- Real-Time Delivery Architecture at Twitter

- Paper: Feeding Frenzy: Selectively Materializing Users’ Event Feeds

- Google: Taming The Long Latency Tail - When More Machines Equals Worse Results

- Did Facebook develop a custom in-memory database to manage its News Feeds? (fan-out-on-read)