How WhatsApp Grew to Nearly 500 Million Users, 11,000 cores, and 70 Million Messages a Second

When we last visited WhatsApp they’d just been acquired by Facebook for $19 billion. We learned about their early architecture, which centered around a maniacal focus on optimizing Erlang into handling 2 million connections a server, working on All The Phones, and making users happy through simplicity.

Two years later traffic has grown 10x. How did WhatsApp make that jump to the next level of scalability?

Rick Reed tells us in a talk he gave at the Erlang Factory: That's 'Billion' with a 'B': Scaling to the next level at WhatsApp (slides), which revealed some eye popping WhatsApp stats:

What has hundreds of nodes, thousands of cores, hundreds of terabytes of RAM, and hopes to serve the billions of smartphones that will soon be a reality around the globe? The Erlang/FreeBSD-based server infrastructure at WhatsApp. We've faced many challenges in meeting the ever-growing demand for our messaging services, but as we continue to push the envelope on size (>8000 cores) and speed (>70M Erlang messages per second) of our serving system.

What are some of the most notable changes from two years ago?

Obviously much bigger in every dimension, except the number of engineers. More boxes, more datacenters, more memory, more users, and more scale problems. Handling this level of growth with so few engineers is what Rick is most proud of: 40 million users per engineer. This is part of the win of the cloud. Their engineers work on their software. The network, hardware, and datacenter is handled by someone else.

They’ve gone away from trying to support as many connections per box as possible because of the need to have enough head room to handle the overall increased load on each box. Though their general strategy of keeping down management overhead by getting really big boxes and running efficiently on SMP machines, remains the same.

Transience is nice. With multimedia, pictures, text, voice, video all being part of their architecture now, not having to store all these assets for the long term simplifies the system greatly. The architecture can revolve around throughput, caching, and partitioning.

Erlang is its own world. Listening to the talk it became clear how much of everything you do is in the world view of Erlang, which can be quite disorienting. Though in the end it’s a distributed system and all the issues are the same as in any other distributed system.

Mnesia, the Erlang database, seemed to be a big source of problem at their scale. It made me wonder if some other database might be more appropriate and if the need to stay within the Erlang family of solutions can be a bit blinding?

Lots of problems related to scale as you might imagine. Problems with flapping connections, queues getting so long they delay high priority operations, flapping of timers, code that worked just fine at one traffic level breaking badly at higher traffic levels, high priority messages not getting serviced under high load, operations blocking other operations in unexpected ways, failures causing resources issues, and so on. These things just happen and have to be worked through no matter what system you are using.

I remain stunned and amazed at Rick’s ability to track down and fix problems. Quite impressive.

Rick always gives a good talk. He’s very generous with specific details that obviously derive directly from issues experienced in production. Here’s my gloss on his talk…

Stats

-

465M monthly users.

-

19B messages in & 40B out per day

-

600M pics, 200M voice, 100M videos

-

147M peak concurrent connections - phones connected to the systems

-

230K peak logins/sec - phones connecting and disconnecting

-

342K peak msgs in/sec, 712K out

-

~10 team member works on Erlang and they handle both development and ops.

-

Holidays highest usage for multimedia.

-

146Gb/s out (Christmas Eve), quite a bit of bandwidth going out to phones

-

360M videos downloaded (Christmas Even)

-

2B pics downloaded (46k/s) (New Years Eve)

-

1 pic downloaded 32M times (New Years Eve)

-

Stack

Erlang R16B01 (plus their own patches)

FreeBSD 9.2

Mnesia (database)

Yaws

SoftLayer is their cloud provider, bare metal machines, fairly isolated within the network, dual datacenter configuration

Hardware

-

~ 550 servers + standby gear

-

~150 chat servers (~1M phones each, 150 million peak connections)

-

~250 mms (multimedia) servers

-

2x2690v2 Ivy Bridge 10-core (40 threads total with hyperthreading)

-

Database nodes have the 512GB of RAM

-

Standard compute nodes have 64GB of RAM

-

SSD primarily for reliability, except when storing video because more storage is required

-

Dual-link GigE x2 (public which is user facing & private which faces the backend systems)

-

-

> 11,000 cores run the Erlang system

System Overview

-

Erlang love.

-

Great language to support so many users with so few engineers.

-

Great SMP scalability. Can run very large boxes and keep the node count low. Operational complexity scales with number of nodes, not the number of cores.

-

Can update code on the fly.

-

-

Scalability is like clearing a minefield. They are generally able to detect and clear problems before they explode. Events which test the system are world events, especially soccer, which creates big vertical load spikes. Server failures, usually RAM. Network failures. And bad software pushes.

-

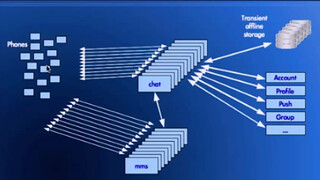

Conventional looking architecture:

-

Phones (clients) connect to chat and MMS (multimedia).

-

Chat connects to transient offline storage. Backend systems hold on to messages while they are in transit between users.

-

Chat connects to databases like Account, Profile, Push, Group, ...

-

-

Messages to phones:

-

Actual text messages

-

Notifications: group subjects, profile photo changes, etc

-

Presence messages: typing, idle, connected/not connected, etc

-

-

Multimedia database:

-

In-memory Mnesia database using about 2TB of RAM sharded across 16 partitions to store about 18 billion records.

-

Messages and multimedia are only stored while they are being delivered, but while the media is being delivered information about the media is stored in the database.

-

-

Run at 1 million connections per server instead of the two million connections per server they did two years ago, generally because the servers are a lot busier:

-

With more users they want to run with more head room on each server to soak up peak loads.

-

Users are more active than they were two years ago. They are sending more messages so the servers are doing more.

-

Functionality that used to be outside these servers was moved to run on them so they are doing more.

-

Decoupling

-

Isolate bottlenecks so they don’t spread through the system

-

Tight coupling causes cascading failures.

-

Backend systems that are deeper in the stack shouldn’t bubble up to the front-end.

-

Everything is partitioned so that if one partition is in trouble the other partitions won’t be impacted.

-

Keep as much throughput going as you can while problems are being addressed.

-

-

Asynchronicity to minimize impact of latency on throughput

-

Allows keeping throughput as high as possible even when there is latency at various points in the system or when latency is unpredictable.

-

Reduces coupling and allows systems to work as fast as they can.

-

-

Avoid head-of-line blocking

-

Head-of-line block is where processing on the first packet in a queue starves all those items queued behind it.

-

Separate read and write queues. Especially where performing transactions on tables so if there’s any latency on the write side it doesn’t block the read side. Generally the read side is going much faster so any blocking will pile up readers.

-

Separate inter-node queues. If a node or network connecting nodes runs into trouble, it can block work in an application. So when sending to different nodes the messages are given to different procs (lightweight concurrency in Erlang) so only messages destined for a problem node are backed up. This allows messages to healthy nodes to flow freely. The problem is isolated to where the problem is. Patched mnesia to do this well at async_dirty replication time. The app sending the message is decoupled from the sending and does not feel any back pressure if there’s a problem with a node.

-

When working with non-deterministic latency a “queuer” FIFO worker dispatch model is used.

-

-

Meta-clustering

-

Note, this section is at about 29 minutes into the talk and is covered very briefly, unfortunately.

-

Needed a way to contain the size of a single cluster and also allow it to span long distances.

-

Built wandist, a dist-like transport over gen_tcp, that consists of a mesh of the nodes that need to talk to each other.

-

A transparent routing layer above pg2 creates a single hop routing dispatch system.

-

Example: two main clusters in two datacenters, two multimedia clusters in two different datacenters, and a shared global cluster between the two datacenters. They all have wandist connections between them.

-

-

Examples:

-

Avoid mnesia transaction coupling by using async_dirty. Most of the transactions are not used.

-

Use calls only when getting back from the database, otherwise casting everything to preserve asynchronous mode of operation. In Erlang, handle_call blocks for a response and messages are queued up, handle_cast doesn’t block because the result of the operation isn’t of interest.

-

Calls use timeouts, not monitors. Reduces contention on procs on the far end and reduces traffic over the distribution channel.

-

When only need best effort delivery use nosuspend on casts. This isolates a node from downstream problems if either a node has problems or the network has problems, in which case distribution buffers back up on the sending node and procs that try to send start to get suspended by the scheduler which causes a cascading failure where everyone is waiting and no work is getting done.

-

Use large distribution buffers to absorb problems in the network and on downstream nodes.

-

Parallelize

-

Work distribution:

-

Need to distribute work over 11,000 cores.

-

Start with a single threaded gen_server. Then created a gen_factory to spread the work across multiple workers.

-

At a certain load the dispatch process itself became a bottleneck and not just because of the execute time. There’s a high fan-in with a lot of nodes feeding into the dispatch process for a box, the locks on the process become a bottleneck with the distribution ports coming in and the process itself.

-

So created a gen_industry, a layer above gen_factory, so that there are multiple dispatch procs which allows for the parallelization of all the input coming into the box as well as the dispatch to the workers themselves.

-

Workers are selected by a key for database operations. For the cases where there’s non-deterministic latency, like for IO, a FIFO model is used to distribute work to prevent head-of-line blocking problems.

-

-

Partition services:

-

Partition between 2 and 32 ways. Most services are partitioned 32 ways.

-

pg2 addressing, which are distributed process groups, is used to address partitions across the cluster.

-

Nodes are run in pairs. One is primary and the other secondary. If one or the other goes down they they will be handling primary and secondary traffic.

-

Generally try to limit the number of procs that access a single ets (built-in term storage) or single mnesia fragment to 8. This keeps the lock contention under control.

-

-

Mnesia:

-

Because they don’t use transactions to get as much consistency as possible they serialize access to records on a single process on a single node by hashing. Hash to a partition, which maps to a mnesia fragment, and ends up being dispatched into one factory, one worker. So all access to a single record goes to a single erlang process.

-

Each mnesia fragment is only being written to or read from at the application level on one node, which allows replication streams that only go in one direction.

-

When there’s a replication stream going between peers there’s a bottleneck in how fast the fragments can be updated. They patched OTP to have multiple transaction managers running for async_dirty only so record updates happen in parallel which give a lot more replication throughput.

-

Patch to allow the mnesia library directory to be split over multiple libraries, which means it could be written to multiple drives, which increases throughput to the disk. Real issue is when mnesia loads from a peer. Spreading IO over multiple drives, even SSDs, gives a lot more scalability in terms how fast the database is loaded.

-

Shrinking mnesia islands to two nodes per island. An island is an mnesia cluster. Even with 32 partitions there will be 16 islands that support a table. Gives better opportunity to support schema operations under load because there’s only two nodes that have to complete the schema operation. Reduces load time coordination if trying to bring one or both nodes up at the same time.

-

Deal with network partitions in mnesia by alerting quickly. They continue running. And then have a manual reconciliation process to merge them together.

-

Optimize

-

The offline storage system used to be a big bottleneck under load spikes. Just couldn’t push stuff to the file system fast enough.

-

Most messages are read quickly by users, like 50% within 60 seconds.

-

Added a write-back cache so messages could be delivered before they had to be written to the filesystem. 98% cache hit rate.

-

If the IO system is backed up because of load, the cache gives extra buffering to deliver messages at full rate while the IO system works to catch up.

-

-

Fixed head-of-line blocking in async file IO by patching BEAM (the Erlang VM) to round-robin file port requests across all async worker threads which smoothed writes in the cases where there was a large mailbox or a slow disk.

-

Keep large mailboxes out of the cache. Some people are in a large number of groups and get thousands of messages per hour. They polluted the cache and slowed things down. Evict them from the cache. Note, dealing with disproportionately large users is a problem for every system, including Twitter.

-

Slow access to mnesia table with lots of fragments

-

The account table as 512 fragments which are partitioned into the islands, which means there’s a sparse mapping of users to these 512 fragments. Most of the fragments will be empty and idle.

-

Doubling the number of hosts caused the throughput to go down. It turned out record access was really slow because hash chain sizes were over 2K when the target is 7.

-

What was happening is the hashing scheme caused a large number of empty buckets to be created and few that were extremely long. A two line change improved performance by 4 to 1.

-

Patching

Ran into contention on the timer wheel. With a few million connections into a single host and each of those is setting and resetting a timer whenever something happens with a particular phone, the results is hundreds of thousands of timer sets and resets per second. With one timer wheel and one lock it was a significant source of contention. Solution was to create multiple timer wheels to eliminate the contention.

mnesia_tm is a big select loop and under load when trying to load tables the backlog could get to a point of no return because of the selective receive. Patch to pull stuff out of the incoming transactions stream and save it to process later.

Add multiple mnesia_tm async_dirty senders.

Add mark/set for prim_file commands.

Some clusters span a continent, so mnesia should load from a nearby node rather than across the country.

Add round-robin scheduling for async file IO.

Seed ets hash to break coincidence w/ phash2.

Optimize ets main/name tables for scale.

Don’t queue mnesia dump if already dumping. Can’t complete a schema operation with dumps pending so if a lot of dumps are queued it wasn’t possible to do schema ops.

The 2/22 Outage

Even with all this work stuff happens. And it happened at the worst time, a 210 minute outage occurred right after the Facebook acquisition.

Did not happen because of load. It began with a back-end router problem.

The router dropped a VLAN which caused a massive node disconnect/reconnect throughout the cluster. When everything reconnected it was in an unstable state they had never seen before.

Finally decided they had to stop everything and bring it back up, which they hadn’t done in years. It took a while to bring everything down and bring it back up.

In the process they found an overly-coupled subsystem. With disconnects and reconnects pg2 can get in a state where it’s doing n^3 messaging. They saw pg2 message queues going from zero to 4 million within seconds. Rolling out a patch.

Release

Can’t simulate traffic at this scale, especially with huge spikes, like News Years Eve at midnight. If they are trying something out that is extremely disruptive it is rolled out very slowly. It will only take a small piece of the traffic. Then quickly iterate until it works well, then roll out to the rest of the cluster.

Rollout is a rolling upgrade. Everything is redundant. If they want to do a BEAM upgrade it is installed and then gradually execute restarts across the cluster to pick up the new changes. Sometimes of it’s just a hot patch it can be rolled out without a complete restart. This is rare. Usually upgrade the whole thing.

Remaining Challenges

Databases get reloaded on a fairly regular basis due to upgrades. The problem with so much data it takes a long time to load and that the loads fail for various reasons at larger scales.

Real-time cluster status & control at scale. The old shell window approach won’t work anymore.

Power-of-2 partitioning. At 32 partitions now. The next step is 64, which will work, but 128 partitions will be impractical. Not much discussion on this point.