VGhlIEFyY2hpdGVjdHVyZSBvZiBBbGdvbGlh4oCZcyBEaXN0cmlidXRlZCBTZWFyY2ggTmV0d29y aw==

Guest post by Julien Lemoine, co-founder & CTO of Algolia, a developer friendly search as a service API.

Algolia started in 2012 as an offline search engine SDK for mobile. At this time we had no idea that within two years we would have built a worldwide distributed search network.

Today Algolia serves more than 2 billion user generated queries per month from 12 regions worldwide, our average server response time is 6.7ms and 90% of queries are answered in less than 15ms. Our unavailability rate on search is below 10-6 which represents less than 3 seconds per month.

The challenges we faced with the offline mobile SDK were technical limitations imposed by the nature of mobile. These challenges forced us to think differently when developing our algorithms because classic server-side approaches would not work.

Our product has evolved greatly since then. We would like to share our experiences with building and scaling our REST API built on top of those algorithms.

We will explain how we are using a distributed consensus for high-availability and synchronization of data in different regions around the world and how we are doing the routing of queries to the closest locations via an anycast DNS.

The data size misconception

Before designing the architecture, we first had to identify the major use cases we needed to support. This was especially true when considering our scaling needs. We had to know if our customers would need to index Gigabytes, Terabytes, or Petabytes of data. The architecture would be different depending on how many of those use cases we needed to handle.

When people think about search, most think about very big use cases like Google's web page indexing or Facebook's indexing of trillions of posts. If you stop and think about the search boxes you see every day, the majority of them do not search massively big datasets. Netflix searches approximately 10,000 titles and Amazon's database in the US contains around 200,000,000 products. The data from both of these cases can be stored on a single machine! We are not saying that having a single machine is a good setup, but keeping in mind all that data can fit on one machine is really important since cross-machine synchronization is a big source of complexity and performance loss.

The road to high-availability

When building a SaaS API, high availability is a big concern as removing all single points of failure (SPOF) is extremely challenging. We spent weeks brainstorming the ideal search architecture for our service while keeping in mind our product would be geared towards user facing search.

Master-Slave vs. Master-Master

By temporarily restricting the problem to each index being stored on a single machine, we simplified our high availability setup to several machines hosted in different data centers. With this setup, the first solution we thought of was to have a master-slave setup with one master machine receiving all indexing operations and then replicating them to one or more slave machines. With this approach, we could easily load balance search queries across all the machines.

The problem with this master-slave approach is that our high availability only works for search queries. All indexing operations need to go to the master. This architecture is too risky for a service company. All it takes is for the master to be down, which will happen, and clients will start having indexing errors.

We must implement a master-master architecture! The key element to enabling a master-master setup is to have a way of agreeing on a single result among a group of machines. We need to have shared knowledge between all machines which stays consistent under all circumstances, even when there is a network split between machines.

Introducing the distributed coherency

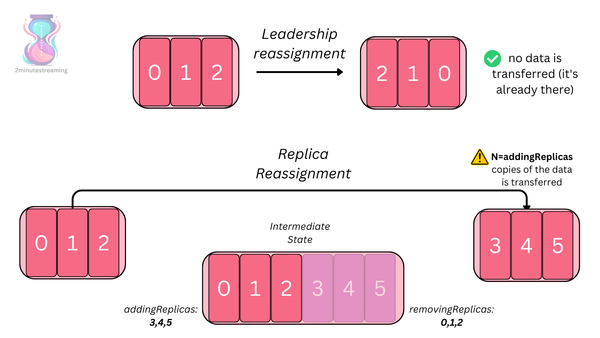

For a search engine, one of the best ways to introduce this shared knowledge is to treat the write operations as a unique stream of operations that must be applied in a certain order. When we have several operations coming at the exact same time, we need to assign them a sequence ID. This ID can then be used to ensure the sequence is applied exactly the same way on all replicas.

In order to assign a sequence ID (a number incremented by one after each job), we need to have a shared global state on the next sequence ID between machines. ZooKeeper opensource software is the de-facto solution for distributed knowledge in a cluster and we initially started to use ZooKeeper with the following sequence:

When a machine receives a job, it copies the job to all replicas using a temporary name.

That machine then takes the distributed lock.

Reads the last sequence ID in ZooKeeper and sends an order to copy the temporary file as sequence ID + 1 on all machines. This is equivalent to a two phase commit.

If we have a majority of positive answers from the machines (quorum), we save sequence ID + 1 in Zookeeper.

The distributed lock is then released.

Finally, the client sending the job is informed of the result. This would be success if there is a majority of commit.

Unfortunately this sequence is not right because if a machine that acquires the lock crashes or restarts between steps 3 and 4, we can end up in a state where the job is committed on some machines, a more complex sequence is needed.

The packaging of ZooKeeper as an external service via a TCP connection makes it really difficult to have it right and requires to use a big timeout (default timeout is set to 4 seconds, representing two ticks of two seconds each).

As a consequence, every failure event, either from hardware or software, would freeze our entire system for the duration of this timeout. It might seem acceptable, but in our case we wanted to test a failure very often in production (like the Monkey testing approach of Netflix).

The Raft Consensus Algorithm

Around the time we were running into these problems, the RAFT consensus algorithm was published. It was clear right away that this algorithm fit our use case perfectly. The state machine of RAFT is our index and the log is the list of index jobs to be executed. I already knew about the PAXOS protocol but did not have a strong enough understanding of it and all the variants to be confident enough to implement it myself. RAFT, on the other hand, was much clearer. If was a perfect match for what we needed and even without stable open source implementations at that time, I was confident enough in my understanding to implement it as the basis of our architecture.

The hardest part of implementing consensus algorithms is making sure there are no bugs in the system. To handle that, I opted for a monkey testing approach by randomly killing processes using a sleep before restarting. To test it even further, I simulated network drops and degradations via the firewall. This type of testing helped us find many bugs. Once we were operating for several days without any problems, I was very confident the implementation was done correctly.

Replicate at application or filesystem level?

We have chosen to distribute the write operations to all machines and execute them locally rather than replicating the final results on filesystem. We made this choice for two reasons:

It is faster. Indexing is done in parallel on all machines, it is faster than replicating the resulting binary files that can be big

It is compatible with multiple regions. If we replicate the files after indexing, we need to have a process that will rewrite the whole index. This means we could have huge amounts of data to transfer. The size of data to transfer is very inefficient if you need to transfer it to different geographic regions around the world (ex. New York to Singapore).

Each machine will receive all write operation jobs in the correct order and process them as soon as possible independently of other machines. This means all machines are assured to be at the same state but not necessarily at the same time. This is because the changes may not be committed on all machines at exactly the same moment.

The compromise on consistency

In distributed computing, the CAP Theorem states that it is impossible for a distributed computing system to simultaneously provide all three of the following:

Consistency: all nodes see the same data at the same time.

Availability: a guarantee that every request receives a response about whether it succeeded or failed.

Partition tolerance: the system continues to operate despite arbitrary message loss or failure of part of the system.

According to this theorem, we compromised on Consistency. We don't guarantee that all nodes see exactly the same data at the same time but they will all receive the updates. In other words, we can have small cases where the machines are not synchronized. In reality, this is not a problem because when a customer performs a write operation we apply that job on all hosts. There is less than one second between the time of application on the first and last machine so it is normally not visible for end users. The only inconsistency possible is whether the last updated received is already applied or not, which is compatible with the use cases of our clients.

General Architecture

Definition of a cluster

Having a distributed consensus between machines is mandatory in order to have a high availability infrastructure but there is unfortunately a big drawback. This consensus requires several round trips between the machines, so the number of possible consensus per second is directly related to the latency between the different machines. They need to be close to have a high number of consensus per second. To be able to support several regions without sacrificing the number of possible write operations means that we need to have several clusters, each cluster will contains three machines that will act as perfect replicas.

Having one cluster per region is the minimum needed for consensus, but is still far from perfect:

We cannot make all customers fit on one machine.

The more customers we have, the less number of write operations per second each unique customer will be able to perform. This is because the maximum number of consensus per second is fixed.

In order to work around this problem, we decided to apply the same concept at the region level: each region will have several clusters of three machines. One cluster can host from one to several customers depending on the size of the data they have. This concept is close to what virtualization is doing on a physical machine. We are able to put several customers on a cluster except one customer can grow and change their usage dynamically. In order to do this, we need to develop and automate the following processes:

Migrate one customer to another cluster if the cluster has too much data or number of write operations.

Add a new machine to the cluster if the volume of queries is too big.

Change the number of shards or split one customer across several clusters if their volume of data is too big.

If we have these processes in place, a customer won't be assigned to a cluster permanently. Assignment will change depending on their own usage as well as the cluster's usage. This means we need a way to assign a customer to a cluster.

Assigning a customer to a cluster

The standard way to manage this assignment is to have one unique DNS entry per customer. This is similar to how Amazon Cloudfront works. Each customer is assigned a unique DNS entry of the form customerID.cloudfront.net that can then target a different set of machines depending on the customer.

We chose to go with the same approach. Each customer is assigned a unique application ID which is linked to a DNS record of the form APPID.algolia.io. This DNS record targets a specific cluster with all machines in the cluster being part of the DNS record so there is load balancing done via DNS. We also use health check mechanisms to detect machine failures and remove them from the DNS resolution.

The health check mechanism is still not sufficient to provide a good SLA even with a very low TTL on the DNS records (TTL is the time the client is allowed to keep the DNS answer cached). The problem is that a host may go down but a user still has the host in cache. The user will continue to send queries to it until the cache expires. It gets even worse because TTL is not an exact science. There are cases where systems do not respect the TTL. We have seen DNS records with a TTL of one minute transformed into a TTL of 30 minutes by some DNS servers.

In order to further improve high availability and avoid a machine failure impacting users, we generate another set of DNS records for each customer of the form APPID-1.algolia.io, APPID-2.algolia.io, and APPID-3.algolia.io. The idea behind these DNS records is to allow our API clients to retry other records when a TCP connect timeout is reached (usually set to one second). Our standard implementation is to shuffle the list of DNS records and try them in sequential order.

Combined with carefully-controlled retry and timeout logic in our API clients, this proved to be a better and cheaper solution than using specialized load balancer.

Later, we discovered the trendy .IO TLD was not a good choice for performance. There are fewer DNS servers in the anycast network of .IO compared to .NET and the ones there were saturated. This resulted in a lot of timeouts that slowed down the name resolution. We have since solved these performance problems by switching to algolia.net domains while keeping backwards compatibility by continuing to support algolia.io.

What about Scalability of a cluster?

Our choice of using several clusters allows us to add more customers without too much risk of impacting existing customers because of the isolation between clusters. But we still had concerns about the scalability of one cluster that needed to be addressed.

The first limiting factor in the scalability of a cluster is the number of write operations per second due to the consensus. In order to mitigate this factor, we introduced a batch method in our API that encapsulates a set of write operations in one operation from the consensus point of view. The problem is that some customers still perform write operations without batching which can have a negative impact on indexing speed for other customers of the cluster.

In order to reduce this performance impact, we have made two changes to our architecture:

We added a batching strategy when there is contention on the consensus by automatically aggregating all write operations of each customer inside a unique operation from the consensus point of view. In practice, this means that we are reordering the sequence of jobs but without an impact on the semantics of the operations. For example, if there are 1,000 jobs pending for consensus and 990 are from one customer, we will merge 990 write operations into one even if there are jobs of other customers interlaced with them.

We added a consensus scheduler that controls the number of write operations per second entering the consensus for each application ID. This avoids one customer being able to use all the bandwidth of the consensus.

Before we implemented these improvements, we tried a rate limit strategy by returning a 429 HTTP status code. It was apparent very quickly that this was too painful for our customers to have to watch for this response and implement a retry strategy. Today, our biggest customer performs more than one billion write operations per day on a single cluster of three machines which is an average of 11,500 operations per second with bursts of more than 150,000.

The second problem was to find the best hardware setup and avoid any potential bottlenecks such as CPU or I/O that could compromise the scalability of a cluster. Since the beginning we made the choice to use our own bare metal servers in order to fully control the performance of our service and avoid wasting any resources. Selecting the correct hardware proved to be a challenging task.

At the end of 2012, we started with a small setup consisting of: Intel Xeon E3 1245v2, 2x Intel SSD 320 series 120GB in raid 0, and 32GB of RAM. This hardware was reasonable in terms of price, more powerful than cloud platforms, and allowed us to start the service in Europe and US-East.

This setup allowed us to tune the kernel for I/O scheduling and virtual memory which was critical for us to take advantage of all available physical resources. Even so, we soon discovered our limits were the amount of RAM and I/O. We were using around 10GB of RAM for indexing which left only 20GB of RAM for caching of files used for performing search queries. Our goal had always been to have customer indices in memory in order to have a service optimized for millisecond response times. The current hardware setup was designed for 20GB of index data which was too small.

After this first setup, we tried different hardware machines with single and dual socket CPUs, 128GB and 256GB of RAM, and different models/sizes of SSD.

We finally found an optimal setup with a machine containing an Intel Xeon E5 1650v2, 128GB of RAM, and 2x400GB Intel S3700 SSD. The model of the SSD was very important for durability. We burned a lot of SSDs before finding the correct model that can operate in production for years.

In the end, the final architecture we built allowed us to scale well in all areas with only one condition: we needed to have free resources available at any moment. It might seem crazy in 2015 to deal with the pain of having to manage bare metal servers, but the gain we have in terms of quality of service and price for our customers is well worth it. We are able to offer a fully packaged search engine with replication to three different locations, in memory indices, and with excellent performance in more locations than AWS!

Is it complex to operate?

Limit the number of processes

Each machine contains only three processes. The first is a nginx server with all our query interpretation code embedded inside as a module. To answer a query, we memory map the index files and directly execute the query inside the nginx worker without communicating to another process or machine. The only exception is when the customer data does not fit on one machine which is rare.

The second process is a redis key/value store that we use to check rates and limits as well as storing real time logs and counters for each application ID. These counters are used to build our real time dashboard which can be viewed when you connect to your account. This is useful for visualizing your last API calls and for debugging.

The last process is the builder. This is the process responsible for handling all write operations. When the nginx process receives a write operation, it forwards the operation to the builder to perform the consensus. It is also responsible for building the indices and contains a lot of monitoring code that checks for errors in our service such as crashes, slow indexing, indexing errors, etc. Depending on the severity of the problem, some are reported by SMS via Twilio's API while others are reported directly to PagerDuty. Each time a new problem is detected in production and not reported we make sure to add a new probe to watch for this type of error in the future.

Ease of deployment

The simplicity of this stack makes deployments easy. Before we deploy any code we apply a bunch of unit tests and non regression tests. Once all those tests are passing, we gradually deploy to clusters.

Our deployments should never impact production nor be visible to end users. At the same time, we also want to generate a host failure in consensus in order to check everything is working as expected. In order to achieve both goals, we deploy each machine of a cluster independently and apply the following procedures:

Fetch new nginx and builder binaries.

Gracefully restart the nginx web server and relaunch nginx using the new binary without losing any user queries.

Kill the builder and launch it using the new binary. This triggers a failure in RAFT on the deployment of each machine with allows us to make sure our failover is working as expected.

The simplicity of operating our system was an important goal in our architecture. We did not want nor believe deployment should be constrained by the architecture.

Achieving a good worldwide coverage

Services are becoming more and more global. Serving search queries from only one worldwide region is far from optimal. For example, having search hosted in US-East will have a big difference in usability depending on where users are searching from. Latency will go from a few milliseconds for users in US-East to several hundred milliseconds for users in Asia without counting the bandwidth limitations of saturated oversea fibers.

We have seen some companies use a CDN on top of a search engine to address these issues. This ends up causing more problems than value for us because invalidating cache is a nightmare and it only improves the speed for a small percentage of queries that are frequently made. It was clear to us that in order to solve this problem we would need to replicate indices to different regions and have them loaded in memory in order to answer user queries efficiently.

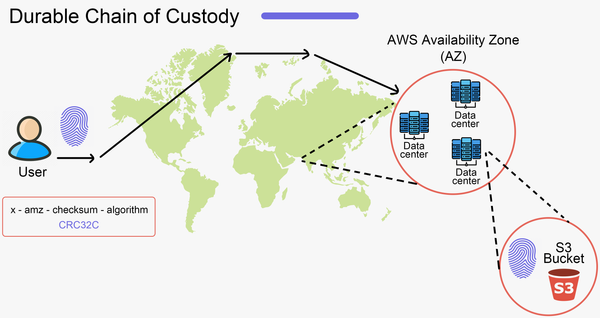

What we need is an inter-region replication on top of our existing cluster replication. The replica can be stored on one machine since the replica will only be used for search queries. All write operations will still go to the original cluster of the customer.

Each customer can select the set of data centers they want to have as a replicate, so a replicate machine in a specific region can receive data from several clusters and a cluster can send data to several replicates.

The implementation of this architecture is modeled on our consensus based stream of operations. Each cluster transforms its own stream of write operations after consensus into a version for each replicate making sure to replace jobs that are not relevant for this replicate with no-op jobs. This stream of operations is then sent to all replicates as a batch of operations to avoid as much latency as possible. Sending jobs one by one would result in too many round trips with the replicates.

On the cluster, write operations are kept on the machines until they are acknowledged by all replicates.

The last part of DSN is to redirect the end user directly to the closest location. In order to do that we added another DNS record in the form of APPID-dsn.algolia.net that takes care of the resolution to the closest data center. We first used the Route53 DNS service of Amazon but rapidly hit its limits.

The latency-based routing is limited to the AWS regions and we have locations not covered by AWS like India, Hong Kong, Canada and Russia.

The geo-based routing is horrible. You need to indicate for each country what the DNS resolution will be. This is a classic approach a lot of hosted DNS providers are taking but in our case it would be a nightmare to support and would not provide enough relevancy. For example, we have several data centers in the US.

After a lot of benchmarking and discussion, we decided upon using NSOne for several reasons:

Their Anycast network is very good and better balanced than AWS for us. For example, they have a POP in India and Africa.

Their filter logic is really good. For each customer we can specify the list of machines that are associated with them (including replicates) and use a geo filter to sort them by distance. We are then able to keep the best one.

They support EDNS client subnets. This is important for us in order to be more relevant. We use the IP of the final user instead of the IP of their DNS server for resolution.

In terms of performance, we have been able to reach global worldwide synchronization at the second level. You can try it out on Product Hunt's search (hosted in US-East, US-West, India, Australia, and Europe) or on Hacker News' search (hosted in US-East, US-West, India, and Europe).

Conclusion

We spent a lot of time building our distributed and scalable architecture and have faced a lot of different problems. I hope this article gives you a better understanding about how we resolved those problems and provides a useful guide on how to design your own services.

I’m seeing more and more services that are currently facing problems similar to us, having a worldwide audience with multi-region infrastructure but with some worldwide consistent information like login or content. Having a multi-region infrastructure today is mandatory to achieve an excellent user experience. This approach can be used for example to distribute read-only replicates of a database that will be consistent worldwide!

If you have any questions or comments, I will be happy to answer.