RXZvbHV0aW9uIG9mIEJhemFhcnZvaWNl4oCZcyBBcmNoaXRlY3R1cmUgdG8gNTAwTSBVbmlxdWUg VXNlcnMgUGVyIE1vbnRo

This is a guest post written by Victor Trac, Cloud Architect at Bazaarvoice.

Bazaarvoice is a company that people interact with on a regular basis but have probably never heard of. If you read customer reviews on sites like bestbuy.com, nike.com, or walmart.com, you are using Bazaarvoice services. These sites, along with thousands of others, rely on Bazaarvoice to supply the software and technology to collect and display user conversations about products and services. All of this means that Bazaarvoice processes a lot of sentiment data on most of the products we all use daily.

Bazaarvoice helps our clients make better products by using a combination of machine learning and natural language processing to extract useful information and user sentiments from the millions of free-text reviews that go through our platform. This data gets boiled down into reports that clients can use to improve their products and services. We are also starting to look at how to show personalized sortings of reviews that speak to what we think customers care about the most. A mother browsing for cars, for example, may prefer to read reviews about safety features as compared to a 20-something male, who might want to know about the car’s performance. As more companies use Bazaarvoice technology, consumers become more informed and make better buying decisions.

Boxes in red are served by Bazaarvoice

Bazaarvoice is integrated on thousands of websites worldwide. During any given month, we’ll serve traffic to over 475 million unique visitors. These visitors will browse, read, and contribute to our corpus of hundreds of millions of pieces of content, ranging from product reviews to questions & answers and even videos of our clients’ products and services. These half billion people will spend a lot of time across our platform, making 10s of billions of pageviews each month. And because we’re on so many high-trafficked commerce sites, our reliability and uptime is of the highest importance. If the Bazaarvoice platform fails, we are affecting the thousands of sites that depend on us. To make all of this work quickly and reliably, we have engineered a highly redundant stack built mostly on top of Amazon Web Services.

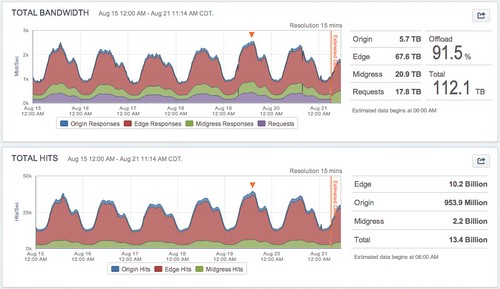

The holiday shopping season is the busiest time for our infrastructure. On “Black Friday” and “Cyber Monday”, we’ll see extremely high traffic, and our load stays high throughout the end of the year and into January. This presents a unique scaling challenge since we have to handle almost 2x our normal (and always growing) traffic for 3-4 months out of the year. This year, we anticipate seeing 60k-65k requests per second during the holiday shopping season.

A week view of pre-holiday Bandwidth and HTTP Requests to our Platform

Humble Beginnings

As with most large software stacks, we started off with a fairly simple architecture. Our initial application was a single monolithic Java application using MySQL as a datastore, all running on a managed hosting environment. As we grew over the years, we built additional applications on the same codebase and bolted on new features. We were early users of Solr, which allowed us to turn MySQL mostly into a key-value store. In addition to Solr, we vertically scaled by just giving the JVM more RAM or by putting the MySQL server on a faster box.

However, as an experienced engineer knows, the easy early gains from vertical scaling quickly become much harder to achieve. So, we started scaling horizontally by simply duplicating our entire stack. We called these “clusters”, and they allowed us to achieve horizontal scaling without having to make large application changes.

Each cluster is a copy of the entire stack with different data.

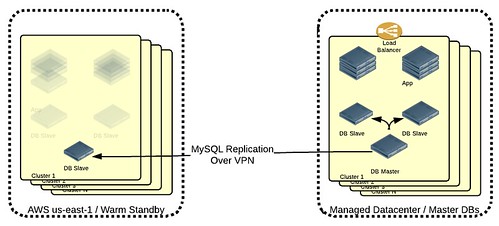

In 2008, when Bazaarvoice was around 3 years old, we experienced some downtime at our managed datacenter that challenged us to become more redundant. One option was to simply find another hosting provider in another geographic region and duplicate all of our servers. But since we were using MySQL, we couldn’t easily go multi-master across regions. Thus our initial plan was just to run MySQL replication from our primary managed datacenter and keep enough capacity to serve production traffic in our backup region, on warm-standby. In the event that our primary datacenter went down, we would update DNS to point to the backup datacenter. This, however, would mean a hard, one-way failover, since the MySQL slaves would have been promoted to masters.

For the slave datacenter to truly work during a disaster, we would need to keep enough spare capacity to serve 100% of our production traffic, effectively doubling our hosting costs without adding production capacity.

Enter AWS

As a young startup at the time, we couldn’t simply double our hosting costs. Amazon Web Services had just dropped “Beta” label from EC2 a month before, in October of 2008, so we thought this might be a great opportunity to save money on our warm standby site while leveraging this new-fangled cloud.

Our strategy when building our redundant backup site on EC2 was mostly the same as using a backup datacenter, except that instead of having to pay for ready-to-go servers sitting in a rack, we just needed to have MySQL slaves running. We could launch instances on-demand if and when we ever needed to fail over to EC2. The cost of doing this was only a fraction of the cost of duplicating our entire production stack at another datacenter.

Our initial foray into Amazon Web Services with only a MySQL slave live.

Fortunately, we never had to implement our failover plan. However, our experience with using EC2 gave us enough confidence to continue to use it when we decided we wanted to serve live traffic out of both our managed datacenter and Amazon’s us-east-1 region. Our data was already being replicated into us-east-1, so we just had to launch application instances and do some minor engineering on our application stack to make it suitable to serve live requests.

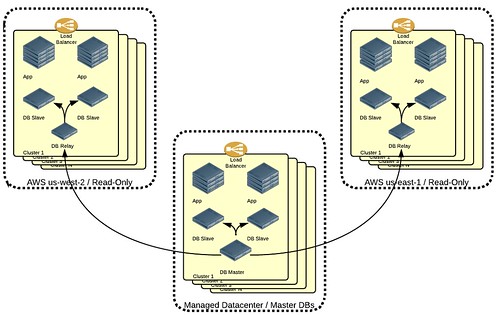

AWS us-east-1 was designed to be read-only to play nicely with MySQL replication. This added in a complication when an end-user submitted a new piece of content into AWS, as MySQL in AWS was read-only. We solved this problem by writing an MQ-based submission queue that replicates the write operation back into our primary datacenter, where we execute the write operation on the MySQL Master. Within a few seconds, the change replicates back out to AWS. This setup worked well and allowed us to double our production capacity while still giving us the ability to completely fail over to AWS, if ever necessary. Soon after, we decided to duplicate our us-east-1 clusters into us-west-2, giving us three live production regions.

MySQL replication from our managed datacenter to two AWS Regions.

To route requests between the two AWS Regions and our managed DC, we employed a DNS-based health-checking system. At EC2, we used HAProxy running on instances with EIPs as load balancers. This gave us one public IP per cluster per region at EC2 and one per cluster at our managed datacenter. We added these origin IPs to a DNS-based health-check pool at our DNS service, which periodically made HTTP requests to each of the origin IPs. The DNS server pulls out any origin IP that failed a health check while balancing the traffic to other regions. A side benefit to this is that we could easily take down a region and do rolling deployments, a region at a time, letting DNS handle shifting traffic around.

Over the years, as we gained thousands of customers and scaled our traffic to billions of pageviews per month, we ended up with hundreds of application servers across 7 clusters running on 3 AWS regions and a managed datacenter. Each cluster had a master database with a large chain of slaves across three regions. If a relay slave along the chain died, we would have to rebuild all of the downstream slaves to reset the master positions. This became very difficult to manage from an Operations perspective. We also had two significant write traffic bottlenecks: the MySQL master running at our managed datacenter and MySQL’s single-threaded replication on all slaves. The slaves routinely fell behind when we had to ingest lots of new data, sometimes by 10 hours or more. We needed to rethink our entire stack.

Starting With a Clean Slate

At the end of 2011, our stack was working, but we wanted to take it to the next level of flexibility, performance, and reliability. We wanted to solve our multi-region replication problem. We wanted to get rid of our individual clusters so that we could do more interesting cross-cluster data relationships. We wanted to release faster. And we wanted to be more cloud native to be able to take advantage of AWS features like autoscaling. This was a lot of change, but we had a new CTO from Amazon Web Services who was very supportive of these initiatives.

Organizational and Technology Changes

Our monolithic Java app was broken up into a set of small services, each supported by a decentralized engineering team. The teams were responsible for the entire service life-cycle, from Development to QA to Operations. In addition, engineering adopted Agile as a development methodology, where previously we were waterfall driven. These changes allowed us to go from what was a highly coordinated 8-12 week release cycle to allowing any team to release at any time. Some teams went on to full continuous integration.

On the technology side, we decided to go all-in with AWS on our new stack. For our system of record, we chose Cassandra for its multi-region replication abilities (DynamoDB fails here) and cloud-native operational qualities. ElasticSearch replaced Solr for similar reasons.

Cloud Engineers

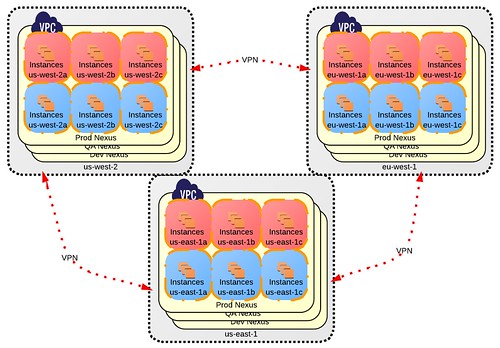

We formed a team called Platform Infrastructure, responsible for building out AWS infrastructure and cloud tools. The Platform Infrastructure team chose to build out AWS in three regions - us-west-2, us-east-1, and eu-west-1 - all within Amazon’s Virtual Private Cloud environment using CloudFormation. The Platform Infrastructure team then built useful micro-services like internal VPC DNS, internal monitoring, centralized logging, costs analytics, and even Netflix-inspired “monkeys” to do tag-conformity enforcement. Because everything used CloudFormation, we were quickly able to spin up identical VPCs for Dev, QA, and Prod environments in three regions within a matter of hours. This new platform, internally named Nexus, took care of infrastructure “heavy-lifting” and offered a solid foundation for application teams to build their services.

Nexus: three environments across nine VPCs in three AWS Regions. VPN from like-environments.

VPC Infrastructure

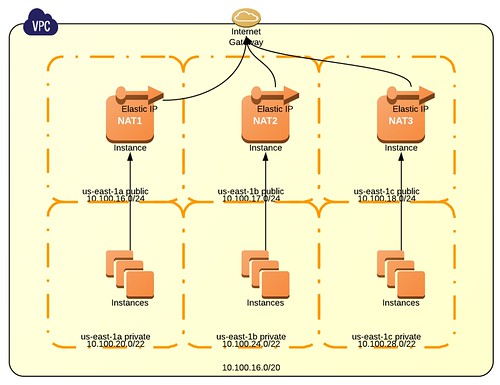

Each of these VPCs looks identical apart from the environment label, the IP ranges, and of course, the dataset. Each VPC used a /20 subnet, divided into three /24 public subnets and three /22 private subnets, utilizing three AZs per VPC. Our CloudFormation templates also configured 1 NAT server per AZ, using an autoscale group of 1, and set the routes so that each private subnet uses its own NAT server for outbound connectivity. This allows for AZ-level isolation and triple the NAT bandwidth instead of using a single NAT server per VPC.

Each VPC uses three Availability Zones, each with its own NAT instance.

We gave every engineer a full AWS IAM account, allowing them unfettered access to Amazon’s wide array of higher level services like Simple Work Flow service, Elastic MapReduce, and Redshift. We chose to optimize for engineer agility over efficiency. But to make sure that our costs don’t get completely out of hand, the Platform Infrastructure team enforces tag conformity. To conform, each team must use two tags across all of their resources: team and VPC. Any AWS resource without proper tags is automatically terminated. One huge benefit of having consistent and enforced tagging is that we were able to determine the exact cost per team.

The Data Layer

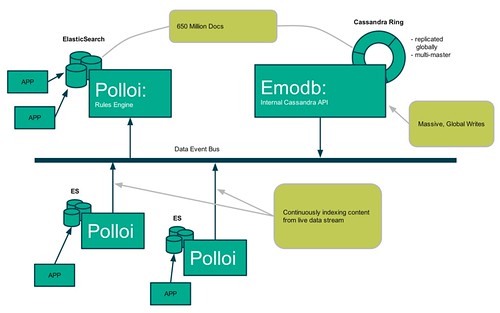

Our Data teams came up with three services for dealing with our massive dataset, all optimized for developer productivity and ease of management. In order to store universal content types without requireing schema migrations and be able to expressively query our data, EmoDB and Polloi were born. Backed by Cassandra, EmoDB is designed to span multiple data centers, using eventual consistency (AP) and multi-master conflict resolution. It exposes a very simple RESTful API that allows users to create "tables" (no schema required - just the name of the table and table placement) and store documents in those tables.

EmoDB still lacked SQL semantics like where, join, group by - basically, anything other than primary key lookup and table-scans. This is where Polloi comes in.

Polloi indexes entity streams into an ElasticSearch cluster. Indexing of each table is done according to the rules specified to Polloi in a very simple Domain Specific Language (DSL). Once Polloi has indexed the data according the these user-specified rules, we end up with a powerful ElasticSearch cluster that can take care of more than primary key lookups. And because each Polloi cluster has a customized ruleset, we have multiple Elasticsearch clusters, each tuned to the needs of the applications that use them. Applications get to leverage the power of ElasticSearch for ultra-fast query responses on petabytes of data.

ElasticSearch still needed to be kept in sync with EmoDB, so we created the Databus to tie EmoDB and Polloi together. Databus allows applications to watch for update events on EmoDB tables and documents, and Polloi listens in on Databus for real-time updates and indexes data appropriately.

EmoDB, Polloi, and Databus

In short, EmoDB provides a simple way to store JSON objects, Polloi indexes fields that are important to specific applications, and Databus notifies Polloi, along with anyone else, on changes to the data.

Application Layer

With the move to a Service-Oriented Architecture, our engineers were no longer constrained to a certain technology stack. Service teams could choose the languages and components that work best for the them. While most teams still choose to implement their service with Java, Python and node.js are two other popular options.

Additionally, teams were free to choose from Amazon’s higher level services like Simple Queue Service (SQS), Simple Notification Service (SNS), and even Simple Workflow Service (SWF). One of our most successful services is now heavily based on SWF, making Bazaarvoice one of Amazon’s biggest SWF users. Using these AWS services enables teams to build their services much more quickly than before.

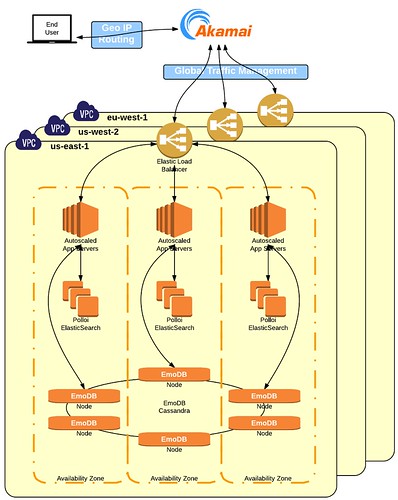

CDN & DNS

Two components that we kept from our legacy stack are our CDN and our DNS-based Global Traffic Management layer. They’ve both worked well, so we didn’t feel the need to make a change for the sake of change.

High level overview of Bazaarvoice’s new stack.

The Future

As we ramp up our production workload on our new stack, we continually look for areas of improvement. We have plans for more automation around application deployments, agent-based anomaly detection, and improving our operating efficiency. We’ve also built some useful AWS tools that we hope to open source in the near future.

Please leave a comment or reach out to me directly if you’re interested in more detail on any aspect of our architecture.